Charlie Bondhus and I will be giving a poetry reading at 7:30 PM on Thursday, Jan. 14, at the Green Street Cafe, located at 64 Green Street (no surprise there) in Northampton, MA. This cozy neighborhood bistro cooks with home-grown herbs and vegetables; I recommend the Sri Lankan vegetable stew.

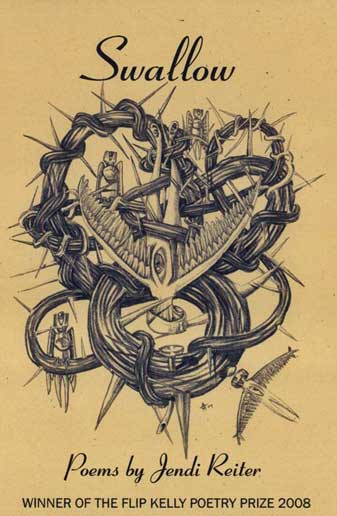

I’ll be reading some of my newer poems and selections from Swallow and A Talent for Sadness. Copies of these books will be on sale, along with my freshman effort, Miller Reiter Robbins: Three New Poets (Hanging Loose, 1990), which features a lovely picture of fierce 17-year-old me.

Charlie’s first full-length collection, How the Boy Might See It, was released last month by Pecan Grove Press. He kindly shares this poem from the book below. It exemplifies the combination of sensuality and spiritual depth that I appreciate in Charlie’s work.

His Sunday Morning Blues

Then the Lord God formed man out of the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being [and] the man knew Eve his wife.

-Genesis 2:7, 4:1

Woke up this

morning cold

kicked the

blankets last night

saw her gone

must’ve stolen out

with the boys

another gathering

lesson, though this time

didn’t wake me up

with a kiss and

touch on the head

like usual.

Don’t feel like checking the fields,

guess I’ll spend the day

in our camel hair bed

and hash this whole thing out.

Funny how

everything I remember before the

sand and the crag looks the way a deer

does, vague behind the gloss

of fog.

I do remember monkeys and mountain goats who

spoke in a voice

similar to our own;

toucans and thrushes that

screeched and warbled in

what must’ve been friendship;

a sense

that everything existed

indefinitely.

As for the woman, she

sometimes talks about tinctured

fruit, every color of a

blush, and uncured leaves–

of peppermint, thyme, rosemary–

something sharper, maybe wiser

that used to float

in the flavor of papayas and kiwis.

Also something more for her

in the sound of the river–

the entire streambed maybe

covered with flutes and shells,

rather than mud and papyrus.

These days though,

everything sounds and tastes

blurry as the dog looked

when we found him

at the bottom of the oasis,

as if we touch and eat

only the colored shadows

of grape, apple, grain–

as if life were lived

forever in twilight.

And still other things,

called to mind by

the branches of a tree–

something in the twist or

the pull, the sober tinge of

bark–

the slope of a leaf–

wondering whether the color is really

green or something that’s not quite

green and if

the edges are really as

pointed or smooth as they

appear.

The gravid clouds that shuffle,

dazed and vapid,

like the feet of an aging God,

across a monotonous sky,

wondering whether or not one could tear

their flimsy substance

between hands or teeth.

Always too, those objects that we

cannot see but still perceive more

readily than rocks and sand,

many of which

I haven’t gotten around

to naming.

Sometimes the woman

cries and throws

herself on the bed

refuses to talk and

I know she’s in pain because

of the blood but we’ve both

cut ourselves before, like once

I tore open my shin on a rock while

climbing after a

goat, and she ripped open

the palms of her hands when she

lost her grip, attempting to pull up

a stubborn vegetable in the garden,

but both of us were still able to speak then

so I know that when she bleeds unbidden,

she must be

stuffed full of

one of those crazy compound things

that we fear

for their power, persistence, and

lack of a name, and that’s

what really hurts.

My greatest fears

stand taller than wheat

when the ground isn’t fertile,

the animals go into hiding, and we

take Cain and Abel,

move to a different place,

and the woman and I find

in each empty, unbreathing land,

no matter how distant,

that the unspoken

is a little more real.

I tremble at these times

when the truth looks the way

that apple grape and grain taste–

should we fall the way some

animals have, stricken by neither

stone nor spear, and the sand were to cover

the crops and the caves crumble to

soil, as they have in the lands we have left,

with no creature capable of maintaining things

as we have, would we be judged unworthy

to return to the place of

sharp taste, musical river, and speaking beast?