“Denise”, a close friend from the days when I was an evangelical fellow-traveler, has long wrestled with the question of the salvation of non-Christians, with the same intensity that I devote to gays-and-God. Her compassionate heart inclines toward as inclusive a vision as possible, yet she also holds the firm conviction that she needs to find Scriptural warrant for any position she takes, in order to be fully obedient to Jesus as Lord.

Perhaps this is where our theological paths diverge most, though I can’t say I’ve really settled exactly what role the Bible does play in my life–some as-yet-unarticulated third way between Denise’s view that “every word in Scripture is exactly as God wanted it to be”, and the liberal view that it’s an important source of history and mythology but not uniquely authoritative.

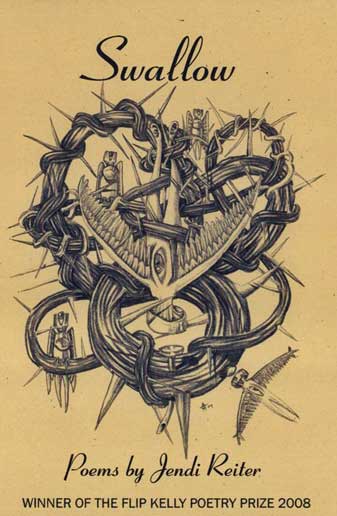

Earlier this month, I had the honor of giving a talk at my church about how my faith and my creative writing inform one another. I sent Denise a copy of my notes, excerpted below, and she sent back some profound questions that inspired another six-page letter. She’s given me permission to share excerpts from our dialogue. I think it encapsulates the core issues in this debate, and some of the reasons why affirming and traditional Christians often seem to be talking past each other.

First, here’s a section from my speech notes:

…When I began this novel, I knew two things in my heart that didn’t make much sense to me: these characters came to me from outside, and I felt the Holy Spirit empowering me to do things I’d never done before. At the time, my mentor was an evangelical writer who said that a book about “sodomy” couldn’t possibly be honoring God. I didn’t have the Biblical expertise to stand up against that. I just couldn’t shake the conviction that these characters had been entrusted to me somehow, and I shouldn’t abandon them in order to secure my spot in heaven.

To make a long story short, this led me on a journey into progressive theology and political activism. I thought more about the reasons we are attracted to certain Biblical interpretations, and the importance of taking responsibility for our emotions and prejudices when we approach the Bible. The human element appeared inescapable. I kept coming back to Jesus’ words, “By their fruits ye shall know them.” You can make clever arguments for just about any interpretation, but if the net result isn’t more love and more equality, you’re probably off-base, whatever the text seems to say.

But along the way, I lost a lot of confidence in the authority of the Bible, and I still wrestle with guilt and uncertainty about my Christian identity because of this. It’s not that I don’t think you can make a good Scriptural case for inclusion, but that I really don’t care as much as I used to, either way. I hope this is more of a way station than a final stance.

How radical it felt to me, how scary, to begin to believe that creative writing is a source of theological knowledge! Though we have Scripture and tradition to tell us what Christians have historically believed, I think we equally need personal, contemporary experience to understand the world to which those doctrines are being applied. The arts, guided by the Holy Spirit, can give us that experience, particularly by widening the circle of our compassion.

There’s a lot of hidden privilege in our theologizing. The question about gay inclusion, for instance, is often framed as “Should we (normal straight people) let them into the church?” Writing, or reading, a story from the perspective of a gay person makes us think twice about assuming that we deserve to be the gatekeepers in the first place. If we’re open to it, we can see that this very different person is just as human as ourselves, and that their life and love has the same potential to manifest the divine spark. This seems to me to be very much in line with the gospel stories, where Jesus constantly reverses the expectations of people who think they’re God’s favorites.

…

And here are Denise’s questions:

The main theme as I read it in all of the above centers around this question: Does an orthodox doctrinal faith operating as “container” for prayer, the creative imagination, and one’s personal living, help or hinder? Do the constraints of a doctrine one doesn’t feel free to question cramp prayer, the imagination, and living, or does an orthodox doctrinal Christian faith free one up from “slavery” to more subjective ideological preferences and agendas for the deeper freedom Paul speaks of, that we have in Jesus Christ?

You know, I’m sure, how much I always resist many of the constraints of a tightly systematized doctrine–both because of my temperament and because I honestly believe the paradox and mystery of the Bible argues against its importance, or even its possibility. At the same time, it seems to me that absolute commitment to Jesus as Savior and Lord has to be at the heart of any true Christianity. How much does that commitment mandate faith in doctrine (as opposed to faith merely in a Person?).

We all have our own issues here– issues that are so crucial to us that any threat to our preferential position shakes us at our very core. For me it has always been the salvation issue, and specifically some perspectives on predestination. For you I sense that the gay issue is the most important, though obviously the salvation issue raises questions for you as well. Speaking just for myself here, I have had to say to Jesus: “If it turns out those aspects of Calvinism which so trouble me are right, and that faithfulness to You means I have to accept their views, then I have to choose You.” I don’t know where you would come out on this “forced choice” were you to be faced with it. I realize that you don’t believe, and probably can’t imagine, you would ever be faced with this choice, since you are so convinced faith in Jesus does not require us to consider homosexual behavior a sin. Quite the opposite, in fact.

But what if it did????? Might it be that one reason you don’t any longer want to read books/arguments contradicting your position is that deep down you wonder if you ever might be faced with that choice, and definitely don’t want to “go there”?

I’m not trying to persuade you of anything here, Jendi. As you know, this is not one of my “issues”. But I just wonder which would come first, were it to come to that? Jesus, or your position on the gay issue?

Here is the first half of my response (with minor edits for style):

Why I Don’t Read Anti-Gay Theology

[1] Non-affirming theologians are often starting from such different premises, regarding the “inerrancy” of the Bible or the “infallibility” of the Catholic magisterium, or an essentialist and complementarian view of gender roles, that there isn’t sufficient common ground for me to get any value from their arguments. I disbelieve in the above-mentioned premises on wholly separate philosophical grounds, not because of the outcomes they might produce for the gay issue.

[2]I don’t need to seek out these arguments because they are all around us in politics and the media, as well as in the writings of conservative Christians whom I read on other subjects. Every time gay people are lobbying for secular civil rights such as marriage, adoption, employment non-discrimination, and anti-bullying programs in schools, Christian leaders who oppose these measures are given an opportunity to air their Biblical position. The Proposition 8 trial alone generated hundreds of pages of this.

Generally, it is not only easier but inescapable for a minority group to know what the majority thinks about them, including the rationales for their subordination. It’s the majority that needs to make a special effort to notice that other perspectives even exist.

[3] Entering one-sided conversations makes me wary. I’d like to flip the question around and ask why non-affirming Christians are so reluctant to listen to gay Christians’ narratives of their own lives? Why, in other words, is it incumbent upon GLBT people and their families to seek out arguments against us, from people who often choose to be uninformed about something we know about first-hand?

A recent instance of this occurred at Harding University, a Church of Christ college in Arkansas. A group of students (anonymously, for fear of retaliation) created a website and print magazine collecting their personal narratives of living with same-sex attraction as Christians at Harding. They spoke about bullying, coerced “reparative therapy”, and suicide attempts—all merely because of their orientation, not sexual activity. The administration responded by blocking the website and declaring the magazine to be in violation of the student handbook.

[4] Let’s concede for a moment, for purposes of this discussion, that non-affirming Christians have the better of the textual argument—namely that the authors the relevant passages in Leviticus and the Epistles intended to condemn all same-sex activity, not only male prostitution and rape of the defeated enemy during wartime, as affirming theologians have argued. That’s a reasonable position, though not the only one.

From that, however, most non-affirming Christians make the questionable leap that the social mores that pertained in Biblical times must be timeless universal commands. This ahistoricism seems to me to foreclose important justice-based critiques of the status quo.

Whichever society you look at, the norms concerning family and sexuality have almost always been formed under conditions of gender inequality—a structural sin that Jesus cared about quite a lot. We conveniently erase a key political dimension of Christianity when we adopt a presumption against progressing beyond ancient social structures.

The direction of the Biblical narrative, especially in the New Testament, is toward ever-expanding equality before God, breaking down barriers based on ethnicity, ritual purity, socioeconomic class, and gender, to name a few. The first Christian communities didn’t perfectly achieve this, and neither have we, but we should try to head in that direction. It would be a shame if we froze that development 2,000 years ago by reifying their imperfections instead of continuing their forward movement.

[5] I would respect, though disagree with, a Christian who conceded that there were no personal pathologies or societal harms associated with homosexuality and that sexual orientation is unchangeable for most people, yet who still believed that the prohibition on same-sex intimacy was a Biblical command, albeit one with no explainable reason behind it except God’s mysterious design.

However, that is hardly ever how the debate unfolds. Probably suspecting that most modern people would not accept such starkly deontological ethics, non-affirming Christian writers/leaders/activists nearly always feel the need to bolster their case with derogatory and long-discredited factual assertions about homosexuals and homosexuality. Such assertions include:

*gay men are pedophiles

*gay people “recruit” others into homosexuality

*gays are incapable of, and/or opposed to, sexual fidelity and monogamy

*gays who want equal rights under civil law are persecuting Christians and interfering with their religious freedom

*gays are unfit parents

*recognizing gay marriage (under civil law, not in the church) will create a sexual free-for-all that undermines marriage and families

*people become gay because they experienced child abuse

*people become gay because their father was emotionally unavailable and their mother was domineering

*all people are naturally heterosexual—”gays” are just confused

*homosexuality can be changed through prayer and therapy

*the “homosexual lifestyle” leads to poor health outcomes and unstable relationships because it’s inherently wrong (in other words, not because of social stigma, parental abuse of gay kids, and discrimination in health care and employment)

Not only do these errors fatally undermine these writers’ credibility in my eyes, but I hold them somewhat accountable for the hate crimes and gay suicides that result from the spread of false stereotypes about gay people as dangerous, perverted, and unnatural.

****

Next in this series: Would I choose Jesus first? Does the question have any meaning? What do you think?