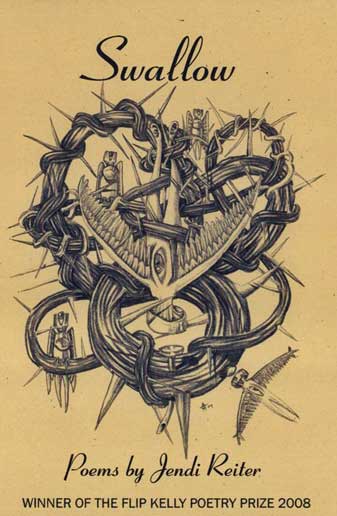

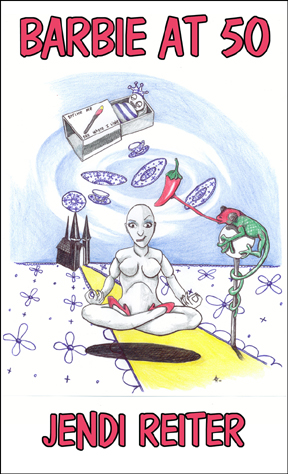

Readers of this blog have enjoyed the poetry and cultural commentary of my prison pen pal “Conway”, whose distinctive artwork graces my chapbook covers. Today I’d like to share an excerpt from my correspondence with another incarcerated writer, “Jon”, a young man who’s on death row in California for an alleged homicide during a robbery. Jon’s pencil drawings of angels, flowers and holiday scenes are good enough for a Hallmark card. He writes fantasy and sci-fi fiction and devotional poetry.

I’ve been trying to send him a copy of Freddy Fonseca’s anthology This Enduring Gift: A Flowering of Fairfield Poetry, which prison officials keep bouncing back because of some undisclosed postal violation. Meanwhile, Freddy emailed me this article from the Boston Globe: “Escape route: The surprising potential of a prison library“, by Avi Steinberg, author of Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian. Steinberg attests to the power of the prison library as a community space where inmates learn to become citizens:

…The problem with the public discussion about libraries in prison is that it’s the wrong discussion. For over a century now, the debate has centered on reading — on which books should, or more often should not, be included on the prison library’s shelves; which books are “harmful” or “helpful”; whether reading is a privilege or a right. In 1867, Wines argued that a book like “Robinson Crusoe” — at the time, the only secular novel permitted in prison — served the cause of criminal rehabilitation. Others fervently disagreed.

But the issue of reading is only one dimension of the question, and not necessarily the salient one. The crucial point of a prison library may not be its book catalog: The point is that it is a library.

The library is a shared public space, a hub, where people spend significant portions of their time, often daily. It is a place inmates work and, in some important ways, live. It is more purposeful and educational than a recreational yard, less formal than a classroom. The prison library gives inmates an organic way to connect to the world, to each other, to themselves as citizens. It’s a small democratic institution set deep within a prison, one they can choose to join.

This is no small matter. The vast majority of prison inmates will eventually be released back into the free world, back into the community. What happens to them once they are out is the critical piece of the corrections puzzle. It doesn’t take an expert to know that a person who lands in prison, a person often already on the margins of society, will grow further isolated from the norms and routines of society while in prison. And yet, at the very same time, and in this very same building, many inmates — often for the first time in their lives — are also quietly becoming enmeshed in an important social institution….

…One of our regular visitors was a twentysomething woman whose 3-year-old daughter was living with a relative during her prison sentence. I’d first lured this inmate to the library by screening new release movie features. After a while, she was in the library at every opportunity, reading books and magazines and watching movies. She was, in other words, an average prison library visitor: a person who had stumbled in, almost by accident, but who ended up quietly but routinely making use of the library’s resources.

When her sentence was drawing to a close, she told me that she was going to miss using the prison library. I replied with the good news: Libraries also exist outside of prison! The idea seemed to surprise her (which surprised me). In her experience, a library, as an institution, was something one encountered in prison. She’d never set foot in a library in the free world.

She left prison, and the library, excited to give it a try. And, she said, she would do for her daughter what had never been done for her: She would bring the child to the public library every week. Just as a prison ID card, stamped with her mug shot, symbolized her civic isolation, I like to think of her public library card as a powerful token of membership back in society. After hundreds of hours logged in the prison’s library, the thought of using a public library now seemed not only plausible to her, but second nature. After her time in prison it was the thought of not using a library that troubled her.

People tend to see a prison as a monolithic institution, a place solely dedicated to locking criminals up. But many inmates experience prison in a more dynamic way, as a clash between institutions. And what I experienced every day was that, in the collision between the institution of prison and the institution-within-the-institution, the library, something constructive and potentially long-lasting was being formed.

Prison libraries aren’t miracle factories. The day-to-day was often far from inspiring. Glossy magazines and mindless movies were, for many, the main attraction. Pimp memoirs were among the most frequently requested books. And yet, even an inmate motivated by nothing more than a desire to watch “The Incredible Hulk” in the back room of the library was much more likely to come across something educational — a book, a program, a mentor — once he entered the library space. Just as important, this inmate was becoming a loyal patron of the library, something he could carry with him to the outside world, and perhaps pass on to his children.

…

I mailed Jon a printout of this article, and his reply in his Jan. 31 letter was so eloquent that I am sharing it below, unedited (spelling and all):

“Litrature of all sorts is probibly the most important thing an incarcerated person can get their hands upon. When a person is in a cell, they’ve plenty of time to think and to reflect. Reading does a number of things for people, for me, concidering all the various materials I’ve read, including classic novels, fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, psychology, numerology, spanish, history, and spiritual, although spiritual, the bible changes lives, my own included.

“The classic litrature is where my ‘self’ education begain in here. Reading these books gave room for self reflection, and also caused me to love reading. Reading can turn some of the most negative of people into patriots, and highly educated (self educated) members of society. I’ve seen it.

“I myself was a very terrible and lost soul when I came into jail. Yet over the years, and throughout books, such as Les Miserabes, A tale of two citys, Frankenstien, the call of the wild, white fang, the phantom of the opera, the three musketeers (and all Dumas’ other books), even Sherlock Holmes, to kill a mockingbird, just to name a few. Throughout books like these, I’ve learned of virtues, such as humor, honer, artistry, and even in many case what is right and what is wrong. Yet most of all I’ve learned of redemption.

“If books such as Hugo and Dickens wrote were readily available, I believe, no, I know that many criminals with reflection from reading would rehabilitate. For anyone to say that a prison library is of doubtful influence, I would say they are ignorant. The problem is a limited library. I truly know that if more state and county prison and jail finances were spent giving inmates access to literature, there would be less repeat offenders.”

****

Moved by Jon’s message? Donate to Books to Prisoners today.