On my campus walk a spring effusion

of spaghetti straps, and—Madonna’s

legacy—the inside outed, too delicate

for the name of straps, tender, silky

bra linguine, tomato-red, celery-green,

slipping off creamy shoulders, or

tangling fetchingly with those spaghetti

straps my daughter informs me, I,

as an older woman, can not wear.

Once, unwittingly,

I draped my navy blazer on

the chairback in my class; two

pale pink shoulder pads plopped

up like obscene pincushions

from the costumer’s shop, abruptly

spotlit. The student they tickled

apologized, but couldn’t stop laughing

each time he looked. Now

I pull my jacket

around me, though it’s hot,

thinking suddenly

of Madame Goldfarb’s Foundation,

Lingerie and Prosthesis Shoppe,

where my mother bought her ordinary

bras, and how the saleswoman—

discussing shoulder

welts, back strain—lifted

her breast into the cup the way

the technician lifts mine onto the plate

for my mammogram, or the butcher

cups the roast he’s about to weigh,

thinking of how

my mother’s hidden back and breasts

even into her ninth decade—

compared with her wizened arms

and face—were shockingly alluring,

olive smooth, unblemished, as I helped her

into the hospital gown.

Originally published in The Evansville Review, this poem was included in Judy Kronenfeld’s chapbook Ghost Nurseries (Finishing Line Press, 2005) and will appear in her full-length collection Light Lowering in Diminished Sevenths, which won the 2007 Litchfield Review Annual Book Contest and will be published next year.

Category Archives: Great Poems Online

“The Approach” and Other New Poems by “Conway”

My correspondent “Conway” has been very prolific this summer, writing poetry inspired by the books and printouts I’ve sent him: T.S. Eliot, Alexandre Dumas, Stephen Dobyns, and even yours truly. Conway is the pen name of a resident in a maximum-security prison in California, where he’s serving 25-to-life for receiving stolen goods under the state’s draconian three-strikes law. Here’s a selection from his recent work:

The Approach

The Sky offers empty promises

smiling with toothy clouds

blades hiding in the invisible wind

pushing forward an orgasmic rain

wide open mouth, stuttering-n-drooling

over the gloriously ravaged land

polished and preened for the dance

electric frustration crackling

instinctive thunder cackling

destructively loud vibrations cuss

at all of mother nature’s fuss

primping for her approaching sun

another beautiful day begun…

****

Pretender

Smell the dust circulating

rumble of gears, chattering wind

pushing past shadows of patience again

pressed faces on clear glass, melted sand

trapped & strapped as time flails

crouching in concrete jails

tumbling hearts in a coin-op dryer

hoping tears will gratify

those moments that pass them by

seasons march with unseen smoke

dawn breaks down upon the broke

strung up tight in spider spun cords

sung all night by distraught mothers

and those muddy misplaced others

pretending to be alive…

One of their pastimes in prison is the “poetry war”, challenging one another to come up with poems or raps on specific topics, often in response to a previous poem by the challenger. I had sent him this ballade I wrote in college, which was inspired by Richard Wilbur’s Ballade for the Duke of Orleans:

Ballade of the Fogg Art Museum

by Jendi Reiter (1990)

The squat museum’s walls decline in plaster;

black iron gates like screens before it rise,

given by graduates now turned to dust or

some more profitable enterprise.

Inside the vaulted halls, the street noise dies

the way the light too fades, as filtered through

too many windows, till the sight of skies

uncovered seems forever out of view.

Upon the wall the carving of some master

hangs as it did over centuries of cries

seeking the aid of this tired saint whose lost or

disputed name was once a healing prize;

saint of the mute, saint of the paralyzed,

of cures some true and some believed as true,

all that their less than truth and more than lies

uncovered seems forever out of view.

Lone stained-glass windows stand, as if the vaster

church fell away and in the rubble lies,

disordered jewels, displayed as if they last were

no necklace, broken when the wearer dies.

Behind them a lit wall the hue of ice,

unchanging light that cannot prove them true,

the sun’s capricious grace that stupefies

now covered and forever out of view.

These corridors wish also to sequester

the wanderer in halls as dim and dry as

the echoes of dead theologians’ bluster

of strict dichotomies that like a vise

close round the listener, until he tries

to follow their imagined bird’s-eye view

of black lines, like this map, where all that eyes

uncover is forever out of view.

Like some grim doctor of the church, the plaster

bust of the founder means to supervise,

mute guardian of a world he tries to master

by over-studying what he is not wise

enough to love; a searching hand that pries

out each thread separately to find the true,

happiest when the tapestry they comprise

is covered and forever out of view.

Above this roof, a bird descends no faster

than snow through shining air, like some demise

so graceful that it isn’t a disaster;

to be a fallen angel would be prize

enough if one could but fall through such skies,

past autumn bursts of leaves’ bright mortal hue

which no recording hand can seize, which lies

uncovered now, then ever out of view.

A wasted hand preserves and petrifies

the gilded tree, flat heaven’s lapis blue.

The leaf must fall, the leaf must improvise,

uncovered now, then ever out of view.

****

In response, Conway wrote the poem below. It plays more loosely with the form but has an immediacy and passion that my old poem lacks. Round #1 to him!

Ballade of Arms Justice

keys that unlock, chains round my waist

and slop I cannot stomach still

we must digest this smell that lingers

until we’re sure we’ve had our fill

for long arms pay, not sticky fingers…

Those white house pillars, fake alabaster

have kept injustice-jackboots laced

we fear the blue steel beanbag blaster

upon the skin burned sentence placed;

It was against forefathers will

to plant, the prosecutions ringers

on the side that fights to steal

laws long arm pays, not sticky fingers…

Law keep your lies, you’re not my master

I cannot be easily replaced

My family reels from this disaster

your long arms pay not, our sticky fingers…

Ned Condini: “In the Farmer’s Hut”

(after Federico Garcia Lorca)

When I feel lonely

your ten years still remain with me,

the three blind horses,

your countless expressions and the little

frozen fevers under maize leaves.

At midnight cancer strode out into the halls

and spoke with the empty shells of

documents,

live cancer full of clouds and thermometers,

with its chaste desire of an apple

to be pecked by nightingales.

In the house where there’s no cancer

white walls break in the frenzy of

astronomy

and in the smallest stables, in the crosses

of woods,

for many years the fulgor

of the burnings glows.

My sorrow bled in the evenings

when your eyes were two stones,

when your hands were two townships

and my body the whisper of grass.

My agony was looking for its dress.

It was dusty, bitten by bugs,

and you followed it without trembling

to the threshold of dark water.

Silly and handsome

among the gentle creatures,

with your mother fractured by the village

blacksmiths,

with one brother under the arches

and another eaten by anthills,

and cancer beating at the doors!

Some nannies give children

milk of nastiness, and it’s true

that some people will throw doves into

a sewer.

Your ignorance is a river of lions.

The day malaria clobbered you

and spat you in the dorm

where the guests of the epidemic died,

you looked for my agony in the grass,

my agony with flowers of terror,

while the voiceless fierce cancer

that wants to sleep with you

pulverized red landscapes in the sheets

of bitterness

and put inside hearses

tiny frozen trees of boric acid.

With your jew’s harps,

go to the wood to learn antennae words

that sleep in tree trunks, in clouds,

in turtles,

in the wind, in lilies, in deep waters,

so that your learn what your country

forgets.

When the roar of war begins

I will leave a juicy bone for your dog

at the factory. Your ten years will be

the leaves that fly in the clothes of

the dead,

ten roses of frail sulfur

on the shoulder of the dawn.

Forgotten, your wilted face

pressed to my mouth, my son,

I will be alone and enter,

screaming, the green statues of cancer.

This poem is reprinted by permission from Wordgathering, an online journal of disability poetry. Ned Condini is a translator and a poetry and fiction writer. Chelsea Editions will soon publish his translation of Carlo Betocchi’s selected works, Awakenings. Among his other awards, he won first prize in the inaugural Winning Writers War Poetry Contest in 2002. His publications include The Earth’s Wall: Selected Poems by Giorgio Caproni, available from Chelsea Editions, P.O. Box 773, Cooper Station, NYC, NY 10276.

Poems for September 11

Today is the sixth anniversary of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Rather than add my own words to a subject that is nearly beyond words, I share below a winning poem from the Winning Writers War Poetry Contest that I judge every year.

SUMMER RAIN

by Atar Hadari

This is the season people die here,

she said, Death comes for them now.

Sometime between the end of winter

and the rains, the rains of summer.

And the funerals followed that summer

like social engagements, a ball, then another ball

one by one, like debutantes

uncles and cousins were presented to the great hall

and bowed and went up to tender

their family credentials to the monarch

who smiled and opened the great doors

and threw their engraved invitations onto the ice

and dancing they threw their grey cufflinks

across each others’ shoulders, they crossed the floor

and circles on circles of Horas

filled the sky silently with clouds, that chilled the flowers.

And funeral trains got much shorter

and people chose to which they went

and into the earth the flowers

went and no one remembered their names

only that they died that summer

when rains came late and the streets emptied

and flags flying on car roof tops

waved like women welcoming the army

into a small, abandoned city.

This poem won an Honorable Mention in our 2003 contest. I also invite you to read these poems that won awards in past years:

Melody Davis, The View from the Tower (2005 HM)

Stacey Fruits, The Choreography of Four Hands Descending (2003 HM)

Raphael Dagold, In Manhattan, After (2002 HM)

Robert Bly Interviewed on PBS

Last week the venerable poet Robert Bly was interviewed on Bill Moyers’ Journal on PBS. Some highlights from their witty, uplifting conversation are below. I recommend watching the video online rather than simply reading the transcript, as Bly’s joie de vivre is an essential part of the experience.

BILL MOYERS: You know, when I first met you, you were just barely 50. And you read this little poem. You remember this one?

ROBERT BLY: “I lived my life enjoying orbits. Which move out over the things of the world. I have wandered into space for hours, passing through dark fires. And I have gone to the deserts of the hottest places, to the landscape of zeroes. And I can’t tell if this joy is from the body or the soul or a third place.”

Well, that’s very good you find that because when you say, “What is the divine,” it’s much simpler to say there is the body, then there’s the soul and then there’s a third place.

BILL MOYERS: Have you figured out what that third place is 30 years later?

ROBERT BLY: It’s a place where all of the geniuses and lovely people and the brilliant women in the– they all go there. And they watch over us a little bit. Once in awhile, they’ll say, “Drop that line. It’s no good.”

Sometimes when you do poetry, especially if you do translate people like Hafez and Rumi, you go almost immediately to this third world. But we don’t go there very often.

BILL MOYERS: Why?

ROBERT BLY: Well I suppose it’s because we think too much about our houses and our places. Maybe I should read a Kabir poem here.

BILL MOYERS: And Kabir?

ROBERT BLY: Kabir is a poet from India. Fourteenth century.

“Friend, hope for the guest while you are alive.

Jump into experience while you’re alive. Think… and think… while you’re alive.

What you call salvation, belongs to the time before death.

If you don’t break your ropes while you’re alive,

you think that ghosts will do it after?

The idea that the soul will join with the ecstatic

just because the body’s rotten–

that’s all fantasy.

What is found now is found then.

And if you find nothing now,

you will simply end up with an apartment in the City of Death.”

I was going through Chicago one time with a young poet and we were rewriting this. And he said, “If you find nothing now, you will seemly end up with a suite in the Ramada Inn of death.” That’s very interesting to see how that thing really comes alive when you bring in terms of your own country. You’ll end up with a suite in the Ramada Inn of death. If you make love with the divine now, in the next life, you will have the face of satisfied desire.

So plunge into the truth, find out who the teacher is, believe in the great sound. Kabir says this, when the guest is being searched for – see they don’t use the word “God”. Capital G, “Guest”. When the Guest is being searched for, it’s the intensity of the longing for the Guest that does all the work. Then he says, “Look at me and you’ll see a slave of that intensity.”

********

BILL MOYERS: You’ve been talking and writing a lot lately about the greedy soul.

ROBERT BLY: I’m glad you caught that. Read this.

ROBERT BLY: “More and more I’ve learned to respect the power of the phrase, the greedy soul. We all understand what is hinted after that phrase. It’s the purpose of the United Nations is to check the greedy soul in nations. It’s the purpose of police to check the greedy soul in people. We know our soul has enormous abilities in worship, in intuition, coming to us from a very ancient past. But the greedy part of the soul, what the Muslims call the “nafs,” also receives its energy from a very ancient past. The “nafs” is the covetous, desirous, shameless energy that steals food from neighboring tribes, wants what it wants and is willing to destroy to anyone who receives more good things than itself. In the writer, it wants praise.”

I wrote these three lines. “I live very close to my greedy soul. When I see a book published 2000 years ago, I check to see if my name is mentioned.” This is really true. I’ve really done that. Yes, I’ve said that. So, in writers, the “nafs” often enter in the issue of how much– do people love me? How much people are reading my books? Do people write about me? Do you understand that? It probably affects you too in that way.

BILL MOYERS: Us journalists? Never.

ROBERT BLY: Never. Okay. “If the covetous soul feels that its national sphere of influence is being threatened by another country, it will kill recklessly and brutally, impoverish millions, order thousands of young men in its own country to be killed only to find out 30 years later that the whole thing was a mistake. In politics the fog of war could be called the fog of the greedy soul.”

********

BILL MOYERS: Are you happy at 80?

ROBERT BLY: Yeah, I’m happy. I’m happy at 80. And– I can’t stand so much happiness as I used to.

BILL MOYERS: You’re Lutheran.

“Art That Dares” to Comfort and Discomfort

Images of Jesus are such common currency in our popular culture that we scarcely notice them, save to afford them a sentimental smile or an eye-roll of aesthetic disdain. From rappers in crucifixion poses on their album covers, to kitsch statues for your little softball player, Jesus is like Mrs. Dash, tossed in to spice up the processed images served up to our jaded palates.

On the one hand, the Incarnation means that Jesus really is standing behind us in the batter’s box (though he didn’t help the Red Sox much this week). We mustn’t get so churchy that we wall off certain areas of life as too mundane for his attention. He still knows when we’re stealing from the cookie jar.

On the other hand, casual handling of Jesus’ image domesticates it, robbing it of its power, as least as often as Jesus-ification elevates the subject matter in question. For me, kitsch images of Jesus can clutter up my mind and block my ability to visualize him as a real, individual, living person.

Kittredge Cherry at Jesusinlove.org has compiled a book of contemporary GLBT and feminist Christian art entitled Art That Dares: Gay Jesus, Woman Christ and More. Samples can be viewed on the gallery page.

I wanted to recommend this project wholeheartedly, but my reaction to the sample works was more complicated. The artworks are presumably meant to be affirming to one group of viewers, and disturbing to others. Jesus, I think, should be experienced as both affirming and disturbing to everyone. Mainstream sentimental Christian art is hampered by its clear-cut message, a trait that this project doesn’t fully escape.

Should the goal of this work be conceived as political rather than devotional, it’s easier for me to overlook the lack of nuance in some of the pieces I saw. It was similarly scandalous to some white Western Christians when people of color tossed out the blonde, blue-eyed image of Jesus in favor of a more African appearance. In Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, male nor female. Most people today would add “black nor white”, but “gay nor straight” (though arguably contained in “male nor female”) is a tougher sell. Paintings like Becki Jayne Harrelson’s The Crucifixion of Christ deliver a shock that can’t be ignored.

Christians who think Cherry’s project is scandalous should go back and read some classic Christian poems, with their ideological blinders off. Start with St. John of the Cross:

On a dark night,

Kindled in love with yearnings

–oh, happy chance!–

I went forth without being observed,

My house being now at rest.

In darkness and secure,

By the secret ladder, disguised

–oh, happy chance!–

In darkness and in concealment,

My house being now at rest.

In the happy night,

In secret, when none saw me,

Nor I beheld aught,

Without light or guide,

save that which burned in my heart.

This light guided me

More surely than the light of noonday

To the place where he

(well I knew who!) was awaiting me

— A place where none appeared.

Oh, night that guided me,

Oh, night more lovely than the dawn,

Oh, night that joined

Beloved with lover,

Lover transformed in the Beloved!

Upon my flowery breast,

Kept wholly for himself alone,

There he stayed sleeping,

and I caressed him,

And the fanning of the cedars made a breeze.

The breeze blew from the turret

As I parted his locks;

With his gentle hand

He wounded my neck

And caused all my senses to be suspended.

I remained, lost in oblivion;

My face I reclined on the Beloved.

All ceased and I abandoned myself,

Leaving my cares

forgotten among the lilies.

(translation courtesy of this website)

And how about this poem by the 17th-century metaphysical poet George Herbert:

Love bade me welcome, yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-ey’d Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

“A guest,” I answer’d, “worthy to be here”;

Love said, “You shall be he.”

“I, the unkind, the ungrateful? ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.”

Love took my hand and smiling did reply,

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Truth, Lord, but I have marr’d them; let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.”

“And know you not,” says Love, “who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

“You must sit down,” says Love, “and taste my meat.”

So I did sit and eat.

“Love”, in this poem, is another name for Christ. Who is male. From the first stanza, we can see that the speaker is obviously male too. Something to think about.

Judith & Gerson Goldhaber: “Noah and the Flood” (excerpt)

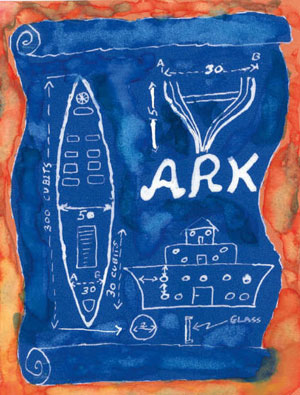

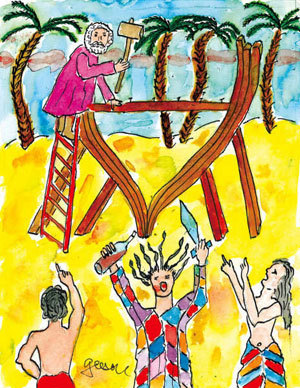

Award-winning poet Judith Goldhaber and her husband, the artist and physicist Gerson Goldhaber, have just released a sequel to their well-received collaboration, the illustrated poetry book Sonnets from Aesop. Their new collection, Sarah Laughed: Sonnets from Genesis, embellishes familiar Bible stories with humorous and mystical elements from midrash and folklore. Willis Barnstone writes, “Sarah Laughed is utterly charming, poem and icon…In the best tradition of imitation it illumines the Abrahamic religions.” The Goldhabers have kindly permitted me to reproduce the following excerpt from their “Noah and the Flood” sonnet sequence:

ii. The Time is Coming

God spoke to Noah when he became a man

and said, “The time is coming — build an Ark;

storm clouds are gathering; soon you will embark

upon the seas, as outlined in My plan.

Make the Ark as sturdy as you can —

line it with pitch, strip gopher trees of bark

to shape the hull, and lest it be too dark

cut windows, and a doorway.” Noah began

to do what God commanded, but worked slowly,

hoping in time the Lord might change His mind

regarding the destruction of mankind.

He begged the wicked to return to holy

customs, but they answered him with jeers.

And thus went by one hundred twenty years.

iii. The Laughing Stock

At last the Ark was finished, and it stood

three hundred cubits long, and fifty wide,

three stories — thirty cubits — high inside

constructed out of seasoned gopher wood,

the laughing stock of Noah’s neighborhood.

“A flood?” the people mocked, “I’m terrified!

Look! Over there! Is that a rising tide

I see? Boo-hoo, I promise to be good!!”

But then Methuselah died, and a malaise

descended on the people, for they knew

that God had stayed His hand until the few

good men still living reached their final days.

A dark cloud veiled the sun; the sky was bleak,

and Noah sniffed the wind and said, “A week.”

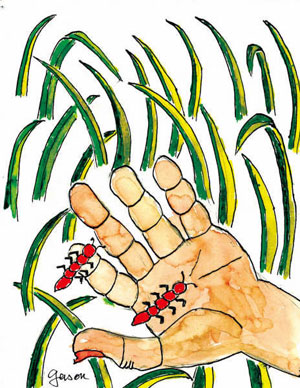

iv. Bird to Bird

Compared to getting humankind to heed

the urgent warnings, putting out the word

to animals was easy. Bird to bird

the news was spread at supersonic speed.

By nightfall all the beasts of earth had heard

the message, and they readily agreed

to group themselves according to their breed

(scaly, hairy, hard-shelled, feathered, furred)

and line up in a queue beside the Ark.

Birds sang and cattle mooed and lions roared

as Noah gently welcomed them aboard

and sealed the door against the growing dark.

At last, on bended knee, nose to the ground,

he gathered up the ants, lest they be drowned.

v. A Mighty Cry

The sun turned black, and lightning streaked the sky,

somewhere behind the clouds a strange light bloomed

and faded, and at last the thunder boomed,

bringing the first drops. Then a mighty cry

arose from those who’d chosen to defy

the warning signs, and callously resumed

their sinful ways. “Even now you are not doomed,”

despairing, Noah cried, “repent or die!”

On board the Ark, through unbelieving eyes

the animals beheld the death of man.

Sworn adversaries since the world began

wept freely as they said their last goodbyes.

Even man’s ancient enemy the snake

shed bitter tears that day for mankind’s sake.

“Pocket Full of Violet” and Other New Poems by “Conway”

In his July 17 letter, Conway writes,

“…The other day while going through work change (strip search) the lady (if you wanna call her that!) searched my lunch (state issue baloney, apple, bread & mustard) well I had put a scooter pie inside the bag, I had purchased from canteen — she said I was not allowed to have it, who knows what (security risk) this would present, ‘the great marshmallow pie war’ so I ate it, you know, destroyed the evidence, literally….

“OK now on to bad news, they shot me down Calif Supreme Court on my writ of Habeas Corpus. So now I must file in Federal court. The basis for the appeal is #1 violation of contract (plea agreement) being as there was no mention of 3 strikes law in original plea bargain in 1987 that if I was arrested for non serious crime I would receive life in prison. I have good federal case law that confirms my argument plus the due process doctrines. It’s hard to get anyone’s ear on this stuff, though. Everyone is so caught up in their own drama they could care less about all the people stuck in here on an illegal law, as long as they have their big screen TV and what-nots….”

From July 26:

“I’ve been going to work almost every day since I got assigned to Vocational Education Clerk. So not much to blabber about, except last Saturday we had a yard down incident (upper yard) I’m lower yard, but they make us all prone out on our belly when they answer an alarm. Any rage, it was 109 degrees and I had my shirt off yard shorts on and was walking the concrete track with a buddy, so we belly crawl off the blazin hot concrete (stayin low) over to the grass field in the center of yard and, were obviously lookin to see who got got, so to speak, and I noticed that the grass was itching real bad, and thinkin it had just been a long time since I laid in the grass, I commented to my buddy “man this grass itches” about that time he looks over at me and says “Dude you got Ants all over you” Sure as heck I’d laid myself smack dab on an ant hole, so we slow crawled sideways and I brushed the critters off me, feelin like the interloper. Crazy huh? I know an Ant can’t move a rubber tree plant, but they sure moved me 🙂 “

Pocket Full of Violet

What love can clutch me

will remain forever, sheltered inside

the refuge of this stone heart

among a lazy river of stars

rising to meet my eyes awake

searching this endless silence

waiting for a break, carefully.

Chances & chains connect our soul

with so many sighs undone, reflecting

glittering like glass marbles

framed in stone and drowned by tears

shuffled savagely by foul years.

Broken fingers of the wind

departed softly unheard, and wept

swept through a lost window

behind another dull evening moon

bringing the bright kite

with a pocket full of violet

waiting beyon this wall

heavy on my heart

promising a new start

in an empty chapel

built by the lean,

mean and broken, spider’ web.

I sat alone in the pew

behind myself, daring my heart

to turn the key and cope

pierce this fierce dark with hope…

********

Spider

A spider hurls his rope up high

into an invisible windless sky.

His silk flag floats down

spinning a sticky town.

He laced up a Butterfly begging to be free

he swallowed her, but won’t feast on me

I wave my middle finger, curse & mock

he smiles and points at his key to my lock.

Someday, he motions, but not just yet

I wonder, do spiders ever regret

forget the paralyzed pleas of their prey

cursing the web, his bite, this Day…

********

Little Brick

This little brick went to prison

that little brick went home

that little brick went missin’

this little brick’s on his own

that little brick the cops hassle

put the little brick back in jail

built a little brick road & a castle

brick by brick straight to hell…

********

The Gavel

When the Gavel came down it glistened

should’ve splintered from the sound

echoing in my mind, still shaking the ground

no one else heard but I listened…

When the gavel came down I bled

while my family mourns, I’m alive still cold

buried in concrete on steel shelf

filed away, story untold

When the gavel came down

we all shut the book on life, in this scene

a library of lost souls

somewhere-n-nowhere

and everywhere in-between

Then the gavel spoke, deafened

I started to choke, lost my mind

for all life to spend

in this library of prison, when

the gavel gave its final decision…

Anne Caston: “A Man, Returning, Will Not Be The Man Who Left”

A world view: for months and months before he left

for war, he’d spoken of it as if to be without one

was to be godless. And then the planes. Four.

Forget a world view. What she wants

today is a table solid enough to set things on:

a lamp, a pitcher, a bowl of lemons.

She wants a dress the color of brandy.

She wants a black lace shawl.

A silk slip. A locket.

But Love, that tenderest tyrant of all,

fastens its necklace of flame

at her throat and she gives herself

over again to the lesser glory of who she is

with him: the glory of a bent spoke

and the rut it fell into.

She imagines him sometimes now

as he must have been then

in that other kingdom of men:

his doll-like face in its little uniform

of death; his shuttered eyes,

opening, closing;

and, underneath the ribs,

in place of an actual heart, the far-off

knocking of the guns that opened him.

Reprinted by permission from the website Why Are We In Iraq?

Caron Andregg: “The Thursday Night Trap Club”

We’re skeet shooting

the potter’s seconds.

The catapult slings

skewed plates, cracked

vases in erratic arcs

across the dry creek canyon.

Each Thursday evening

we obliterate

the week’s mistakes.

When the pellet-spread connects,

explodes a shrapnel star

it’s an absolution.

Lucinda’s been casting

reproductions of Egyptian

bowls with tiny feet.

One seems near perfect;

but when I set it

on the trap-box edge

it lists, daylight gleaming

beneath the toes of one foot.

When wet and forming

it must have rested

on a warp, something

not quite level in the firing.

It seems somehow unfair

this small, lame thing

wound up in the slag-box

destined for buckshot

just because it totters.

And it strikes me

how much easier it is

to love a flawed object –

the supplicant’s posture

like a pair of cupped hands;

the sloped bowl tilted in offering;

its little feet of clay.

Caron Andregg is co-editor of the fine journal Cider Press Review, which is accepting submissions through Aug. 31. They also sponsor a poetry manuscript prize open for entries Sept. 1 (deadline Nov. 30). This poem was originally published in Rattle.