This video will explain why I turned off the comments mechanism on this blog:

Great humor often contains insights into serious issues. What is the difference between an argument and mere contradiction or abuse? And what motivates us to respect some arguments, while blocking out the possibility that others might be legitimate?

We may resort to bare contradiction when it’s too frightening to face new interpretations of a text that once seemed clear to us. Refusal to engage with the argument can be a way of denying that there could be other possibilities. Sadly, it also bypasses an opportunity for self-knowledge.

As long as we pretend that there is only one possible viewpoint, we don’t have to examine the desires, fears, vanities, or misunderstandings that spur us to cling to that viewpoint. Nor do we confront the power imbalance between us and the questioners–the privilege that puts us in a position to interpret their lives in the first place, rather than the other way around.

Abuse takes this strategy a step farther. Because ours is the only possible interpretation, anyone who disagrees must be disobedient or perverted. Our own anger (or revulsion, or fear of losing something special to us) becomes objectified, masked by the authority of the text. It is not a personal feeling for which we must take responsibility, whereas the other side has only selfish personal feelings.

Before we as Christians can conduct a fruitful and faithful discussion about issues on which we disagree, we must be honest with ourselves and one another about the passions behind those issues, and consider which emotions are the most appropriate guides to choosing between one interpretation and another. Perfect love casts out fear.

Category Archives: Notable Quotes

What Children Hear in Church

Sara Pritchard’s first novel, Crackpots, won the prestigious Bakeless Prize from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 2002. I’ve put the book on my wish list after savoring this hilarious excerpt, “The Very Beautiful Sad Elegy for Bambi’s Dead Mother”, on her website. This is the story of a child who is doomed to become a writer, who relishes words with a physical delight, even (or especially) when she’s a little unclear on what they mean. My favorite part:

“I believe in the holey ghost, the holey Christian church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting, Hey men!” you say to yourself, bouncing a ball, walking Go-Jeff on a make-believe leash, jumping rope, hopping on one foot, skipping to school, whumping your slinky down the stairs. “The life everlasting, Hey men! The life everlasting, Hey Men! The holey Christian church. The holey Christian church. The holey-moley, roley-poley, holey Christian church.”

Now it’s Thanksgiving vespers, and after your favorite poem, the Apostles’ Creed, everyone is singing one of your favorite hymns, “Bringing in the Cheese,” their voices happy and cheerful, their faces kind in the yellow light. Mrs. Kline, at the pipe organ, is trying to keep up, her crow wings flapping, her feet going one direction, her hands the other.

Bringing in the cheese, bringing in the cheese,

We shall come rejoicing, bringing in the cheese.

You stand next to Albertine in the children’s choir and sing as loud as you can, sort of shouting. You sing with your top lip curled under and your top teeth sticking out like a mouse because this is a hymn written by church mice, and you are pretending to be one of them as you sing. Gus and Jock—from Cinderella—probably had a part in composing this wonderful hymn. They probably know it by heart. They are probably singing it right now at the top of their lungs in one of the dark, echoing alcoves of Riverview Lutheran Church, maybe over to your right there behind the baptismal pot, standing on a big hunk of Swiss cheese.

The hymn is over. The congregation claps shut their hymnals, but everyone remains standing as Mason, an acolyte, puts out the altar candles with the big candlesnuffer on a pole. Reverend Creech raises his arms like he, too, is about to fly. “Let us pray,” he says, and then the beautiful words wash over you, the words you will always remember all the long days of your life and whisper to yourself when you’re afraid, when you’re alone, when all the sadness of being human gathers itself around you:

May the piece of God, which passeth all understanding,

keep your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus, Amen.

For many, many years you ponder just exactly which piece of God Reverend Creech might be referring to, but for now, you forget about all that because the choir is filing out and everyone is singing your very most favorite song in the whole world, the one your mother plays for you on the piano at bedtime, and your father has taught you and Albertine to sing in two-part harmony:

Now the day is over, night is drawing nigh,

Shadows of the evening steal across the sky.

Now the darkness gathers, stars begin to peep,

Birds and beasts and flowers soon will be asleep.

Thru the long night watches may thine angels spread

Their white wings above me watching ’round my bed

Grant to little children visions bright of Thee

Guard the sailors tossing on the deep blue sea.

Comfort every sufferer watching late in pain

Those who plan some evil, from their sin restrain

Jesus, give the weary calm and sweet repose

With thy tenderest blessing may my eyelids close.

* * * * *

1958—With very little coaxing and carrying, and only minor scratches, a big orange cat follows you and Albertine home from school. A big orange cat with silky fur and a big round pumpkin head. An orange cat who walks around the house rubbing her head on the legs of everything, including you. She walks in and out your legs, in and out, and her tail goes up your dress and makes you giggle.

“Our cat must have a very beautiful name,” Albertine announces. “Princess!” she exclaims. “Here, Princess! Here pretty Princess Kitty!”

“Kyrie Eleison!” you call, after the beautiful and mysterious words of the kyrie sung in church. “Here, Kyrie,” you call, crawling across the carpet toward your cat. “Here Kyrie! Kyrie Eleison!”

“Daisy,” Albertine says resolutely. “DAISY BUTTERCUP.”

“Here Dona, Here Dona,” you persist, “Here Dona Nobis Pacem!” and Albertine rolls her eyes so far back into her head they disappear completely. Only the whites—like Orphan Annie’s—show.

“Panis Angelicus?” you pout and beg, “Adeste Fideles? Agnus Dei?”

For many hours that night, you lie awake, wandering through the enchanted forest of all the words you know, bumping into trunks and branches, tripping over roots and stumps, searching for the perfect name for your beautiful orange cat: mimosa, marmalade, gladiola, peony, poppycock, forsythia, taffeta, pinochle, piano forte, aspen, pumpkinseed, Leviticus Numbers, lickety-split, fiddlesticks, Worcestershire, nincompoop, whippoorwill, whippersnapper, Fridgedaire, DeSoto, squirrel, pollywollydoodle all the day . . . and on and on. And then . . . lying on its back, humming “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” kicking its feet and doing the back stroke around your brain, you find it: the perfect name for your cat. So you can go to sleep now. But come morning, you wake up in a panic because the perfect name you’ve now forgotten! You should have written it down! Your heart is racing: mimosa, gladiola, peony, forsythia, taffeta, squirrel . . . Oh, praise the Lord, there it is! You run downstairs, but . . .

Your cat is gone.

“He wanted out,” Mason mumbles, dripping a big, sloppy servingspoonful of Wheaties up to his mouth and never looking up from the cereal box he’s reading.

Visit Sara Pritchard’s website here to find out about her new collection of linked stories, Lately.

“Nature” a Moving Target for Theologians

Austen Ivereigh, a columnist on the website of America: The National Catholic Weekly, made some insightful comments on the Church’s changing understanding of what is “natural” in his Christmas Eve column, “Gays, Galileo, and the Message of the Manger”. Excerpts:

The BBC has the correct headline on Pope Benedict’s curial speech story. “Pope attacks blurring of gender” is far more accurate than all those headlines claiming that “saving gay people is as important as saving the rainforests”…

The essential theological point in the Pope’s intriguing address is that going green while erasing God from Creation is a contradiction. Nature, he says is “the gift of the Creator, with certain intrinsic rules that offer us an orientation we must respect as administrators of creation.”

And he goes on: “That which is often expressed and understood by the term ‘gender’ in the end amounts to the self-emancipation of the human person from creation and from the Creator. Human beings want to do everything by themselves, and to control exclusively everything that regards them. But in this way, the human person lives against the truth, against the Creator Spirit.”

It’s worth placing this papal observation alongside the tribute Benedict XVI paid last Sunday to Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) on the 400th anniversary of the condemned astronomer’s telescope.

Galileo, you will recall, was declared a heretic by the seventeenth-century Church for supporting Nicholas Copernicus’ discovery that the Earth revolved around the sun (church teaching at the time placed the Earth at the centre of the universe). For centuries the Galileo condemnation has been used by secularists as a symbol of all that is incompatible between faith and science.

Last weekend, the Vatican sought to reverse that symbolism, building on Pope John Paul II’s 1992 apology and dusting off Galileo as a shining representative of faith and reason working together….

…I can’t help but spot an irony.

Galileo was condemned, at the time, because he was held to subvert the God-ordained nature of things. One can imagine Pope Urban VIII in 1633 using words similar to Pope Benedict’s to the Curia: that nature has “certain intrinsic rules that offer us an orientation we must respect as administrators of creation.”

But it wasn’t long before the “intrinsic rules” were overturned by the evidence. It turned out that putting the Earth at the centre of the universe was not God’s plan at all.

Mark Dowd, gay ex-Dominican and strategist for the Christian environmental group Operation Noah, is widely quoted in UK press reports as saying that in his curial speech Benedict XVI betrayed “a lack of openness to the complexity of creation” — in other words, that papal faith in the fixity of male-female gender roles may be misplaced.

At the moment, there seems little room in the Catholic Church’s “human ecology” for a possible divine purpose for homosexuality — just as in the seventeenth century there wasn’t much space for the idea that God has arranged the universe with the sun at its centre. It would be syllogistic to suggest that because the Church was wrong on the second it will turn out to be wrong on the first.

But it’s striking how the homosexual orientation appears in church teaching as “intrinsically disordered” — in other words, as contrary to the way God arranged the universe — in the same way as the Copernican view appeared in the seventeenth century.

And it isn’t a bad thought, at Christmas, to remember that the Creator of the Universe is capable of subverting its laws for the sake of His creatures.

Things are never so finally fixed that God can’t rearrange it all. The arrogance of scientists, of clergy, of the wise, our own arrogance — all get dethroned tonight by the Great Event: the manger-child, born of a refugee couple and the Holy Spirit, in a cave, in a place somewhere off the map, to where the centre of the Universe quietly relocates. Happy Christmas.

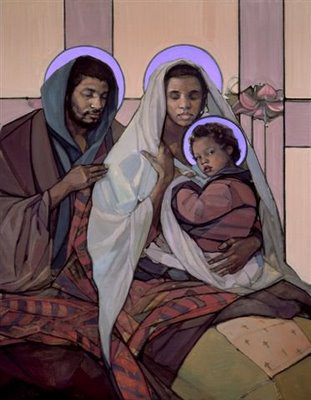

AltXmas Art Envisions Holy Family of Color

Kittredge Cherry’s Jesus in Love blog is running a series of artworks that look at the imagery of the Christmas season through the lens of poverty, racial and gender justice. The beautiful and thought-provoking images are accompanied by Kitt’s daily Advent meditations. She’s kindly given me permission to reproduce today’s painting, “The Holy Family” by Janet McKenzie.

Copyright 2007 Janet McKenzie

Collection of Loyola School, New York, NY

About this painting, Kitt writes:

…Sometimes McKenzie’s art sparks controversy. Her androgynous African American “Jesus of the People” painting caused an international uproar after Sister Wendy of PBS chose it to represent Christ in the new millennium in 2000. However, McKenzie says that the responses to “The Holy Family” have been accepting and positive, perhaps because it was commissioned and wholeheartedly supported by the Loyola School in New York.

“As a school run by the Jesuits, it was important to them to have such an image, one that reflects their ethical and inclusive beliefs,” McKenzie explains. “ ‘The Holy Family’ celebrates Mary, Joseph and Jesus as a family of color. I feel as an artist that it is vital to put loving sacred art — art that includes rather than excludes — into the world, in order to remind that we are all created equally and beautifully in God’s likeness. Everyone, especially those traditionally marginalized, needs the comfort derived by finding one’s own image positively reflected back in iconic art. By honoring difference we are ultimately reminded of our inherent similarities.”

The Vermont-based artist had built a successful career painting women who looked like herself, fair and blonde, before her breakthrough with “Jesus of the People.” At that time she wanted to create a truly inclusive image that would touch her nephew, an African American teenager. “The Holy Family” continues the process of embracing everybody in one human family created in God’s image.

Read the full post here.

The Gospel According to GQ

This summer, the men’s magazine GQ published a lengthy and respectful profile of Gene Robinson, the Episcopal bishop of New Hampshire, whose election in 2003 brought the Anglican Communion’s disagreements over homosexuality into public view. Robinson’s patience, charity and love shine out from this well-written article by Andrew Corsello.

One might expect a magazine like GQ to hold its subject’s faith at arm’s length, playing to the cynical sophisticates in their target audience. But Corsello’s even-handed writing never invites the reader to sneer that the God whose love Gene Robinson feels, and whose will he tries to obey, is an irrational construct he would be better without. Unlike many of the bishop’s conservative Christian detractors, this secular magazine accepts the genuineness of his love for Jesus and humanity–a love borne out by Robinson’s activism on behalf of the poor, and his desire to reconcile with Christians who have abused and threatened him.

By the time Gene Robinson ended his marriage and came out of the closet, New Hampshire’s Episcopalians had known him for eleven years. They were shocked but, with a few exceptions, not up in arms. The man had brought love, transparency, and the truth as he knew it to their children and their families for more than a decade. Why would he stop now?

One of those exceptions was a fellow priest named Ron Prinn, whom Robinson had known and worked with for years. “I understand you’ve done this because you’re a…what?” Prinn demanded.

“A homosexual, Ron. I’m a homosexual.”

“I just don’t understand it,” Prinn said. “Boo. The girls. I don’t understand.”

Robinson said he wasn’t demanding or even asking Prinn to understand. “Just be in communion with me. That’s all I ask.”

“I don’t think I can,” Prinn said. “I just don’t know if it’s permissible.”

Terrible words. To the unchurched, “in communion” is the kind of term that can pass through the senses without finding purchase. But to those who have grown up in the church, not to mention those who devote their lives to it, to be told by a man of the cloth that you are not worthy of sharing Communion is to be cast out by one’s own flesh and blood; it is to be told that you are unworthy of salvation.

And then there was that word. Permissible. It was a word that implied the primacy of doctrine—canons, rules, rote adherence to the letter of the law—over the kind of questing, empathetic faith Robinson had practiced all his life. Not only was Gene Robinson being told he was unworthy of communion but also that he fundamentally misunderstood what it represented….

Not long after moving into his new home with Mark Andrew, Robinson sent Ron Prinn a letter. The two had worked for several months on a committee, after which Gene and Mark hosted a dinner for committee members and their spouses. Prinn had answered the invitation with silence, so Robinson sat down and wrote everything he’d learned about fear.

“I told him what I’d learned from my own life, and from those of everyone to whom I’d ever been a pastor—that the fear is always worse than the reality. You know how when you’re a kid lying in bed and you just know there’s something in the room with you, and how frightening that is—but how the thought of turning on the light is somehow even more frightening? So I wrote, ‘Ron, I don’t think you’re afraid of what you think you’ll see if you come to my home. You might think you are—that you’re afraid of all the pictures of naked men we must have on every wall. But I think you’re afraid of what you won’t see. I think you’re afraid that you won’t see those pictures, that what you’ll see is actually quite boring. Which it is. And I think you’re afraid of what that might mean. So let me tell you now: What you will see when you come here is a Christian home. You have a standing invitation.’ ”

Prinn never acknowledged the letter, but a year later the two men met at a clergy conference. Robinson was now Canon to the Ordinary—the New Hampshire diocese’s second in command. Prinn took Robinson’s extended hand but said nothing in response to his hello. Something was very wrong—he wouldn’t let go of Robinson’s hand. Just kept it gripped while gazing into Robinson’s face. His voice trembled when he spoke.

“I have done everything the church has asked me to, I have believed everything I have been told to believe, and I am unhappy.” He seemed to be talking at himself as much as at Robinson. “And here you are living your life the way the church says you shouldn’t. And…look at you.” Before Robinson could muster a response, Prinn withdrew his hand, turned, and left the room.

“Later in the conference, the bishop got called away, so it fell to me to celebrate the Eucharist,” Robinson recalls. “I was halfway through the prayer of consecration when I realized he was going to have to present himself to me for Communion. Sure enough, I looked down and there he was in line. When he knelt, I thought he might cross his hands over his chest, so as not to receive the host from me. But then he put out his hands. Not for the host but for me. So I knelt with him, and right there at the altar rail he took me into his arms.”

Several years later, Prinn worked on a committee tasked with deciding whether the diocese’s annual clergy and spouse retreat should be renamed, with “partner” replacing “spouse.” Prinn was torn. Though he had come back into communion with Robinson, he still didn’t approve of what he saw as the man’s poor decisions—and he still hadn’t brought himself to cross his doorstep. As Prinn saw it, a gay clergyman, an individual, was one thing; the institutionalization of “gayness” in the church, even semantically, was another. Grudgingly, he placed a call to Mark Andrew.

“Would it even mean anything to you?” he asked. “I mean, you already attend the conference. It’s just a word, right?”

“A word is never just a word,” Andrew said. “It would mean everything.”

Prinn made the change.

By the time Prinn finally accepted one of Gene’s group-lunch invitations, three years ago, Parkinson’s disease had ravaged his body. He could no longer eat—liquid nutrients had to be pumped directly into his stomach through a stent—and had neared the point where he could no longer walk or talk. Another of the guests ushered Prinn and his wife, Barbara, through the garage, where Gene and Mark had installed a handicap lift years before. When he rolled his walker into the kitchen, Prinn beheld Gene with a bewildered look. A gurgling sound emerged from his throat. Barbara put an ear to her husband’s mouth, then translated.

“Ron wants to know who in your family is handicapped.” No one, Gene said.

It clearly pained Prinn to muster the words, but he managed.

“Who did you build that lift for?”

The lift had been used only once before. Gene hadn’t thought twice about installing it. His theology of inclusion had structured not only his ministry but his idea of what a living space should be; the lift hadn’t been built with anyone particular in mind.

“We built it for you,” Gene said.

Prinn began to cry quietly, then motioned for Gene to come close. When he did, Prinn whispered that he wanted Robinson to kiss him.

Barbara Prinn says that in her husband’s final months, when he could no longer speak, Robinson would sit with him in silence for hours at a time, holding his hand and, before taking his leave, kissing the dying, smiling man on the crown of his head.

I suggest reading this article for background before moving on to Robinson’s recent book, In the Eye of the Storm, which has much to recommend it, but is somewhat too reticent for an autobiography (he is Episcopalian, after all!). Inspiring but disorganized, it reads more like a collection of sermons on the social gospel than a truly systematic defense of gays in the church. I was glad to discover, though, that Robinson holds orthodox views on the Trinity, Incarnation and Resurrection, contrary to the scare tactics of conservative Christians who argue that acceptance of homosexuality leads inexorably to theological liberalism and relativism.

Blogger Mars Girl has written a good review of Robinson’s book, in which she also explains why she’s such a passionate straight ally. She speaks for me when she says:

Too often, homosexuals are driven from a faith-based life because their home churches spurn them as sinners of the worst kind. It was really refreshing to read this book and get some insight to a great man who has found a way to challenge the people in his faith as well as unattached readers like me who just seek social justice for homosexual and transgendered people.

He had me at one of the first paragraphs in his book when he stated in better words what I’ve always thought in my heart:

Everyone knows what an “ism” is: a set of prejudices and values and judgements backed up with the power to enforce those prejudices in society. Racism isn’t just fear and loathing of non-white people; it’s the systematic network of laws, customs, and beliefs that perpetuate prejudicial treatment of people of color. I benefit every day from being white in this culture. I don’t have to hate anyone, or call anyone a hateful name, or do any harm to a person of color to benefit from a racist society. I just have to sit back and reap the rewards of a system set up to benefit me. I can be tolerant, open-minded, and multi-culturally sensitive. But as long as I’m not working to dismantle the system, I am a racist.

Similarly, sexism isn’t just the denigration and devaluation of women; it’s the myriad ways the system is set up to benefit men over women. It takes no hateful behavior on my part to reap the rewards given to men at the expense of women. But to choose not to work for the full equality of woman in this culture is to be sexist. (p. 24, bold emphasis mine)

Robinson goes on to equate this same argument with those who sit back and benefit from a hetersexually-centered society but do nothing to help change the system for equality for homosexual and transgender people. This argument is why I fight so hard for this cause when often times people ask–or want to ask–why I care so passionately about this issue when it’s not really my issue to fight. As a Unitarian Universalist, one of the seven principles to which I have agreed is the inarguable “inherent worth and dignity of every person.” This is the only principle of the seven principles I ever remember when asked, and that’s because it’s the one that resonates to my heart the strongest.

In reading the book, you have to swallow a lot of Christian dogma and faith. For someone like me, it’s hard not to roll my eyes and squirm when he discusses how every human being is saved through Jesus Christ. This man is certainly as evangelical as any Sunday morning preacher when it comes to his love for God and Jesus, and you can feel it hitting you full blast from every page. However, you also really understand the man Robinson is and you understand how deeply he believes. You can’t help but respect that. I can see why he must be such a great priest that he elevated to bishop: This man believes and he knows he’s saved and he wants to tell you all about how you can join him on this journey. I almost did want to join him on this journey. In fact, by the end of this book, I was bound and determined to visit the Episcopal church in Kent. I thought if the people of his faith thought as he did, even a questioning, sometimes-believer/sometimes-atheist person like me could join the bandwagon without much notice.

I haven’t gone to that church just yet, not even to peek for education’s sake. I’m happy where I’m at and where I’m at gave me the ability to appreciate Robinson’s words in ways I never could have even two years ago. He made me want to be Christian like no other preacher has before….

Even as a heterosexual, I can relate on some level to being forced to hide aspects of oneself from the public eye to fit in. As a child in middle and high school, I submerged aspects of my personality in order to fit into the group mind of the adolescents in my high school. Though trite compared to having to hide your own sexuality, the toll to my mentality was detrimental. I found myself doubting my own self-worth and it took a lot of years to undo the damage I did. I guess that’s part of the reason I’ve gone the complete opposite direction as an adult in highlighting the unique aspects of my personality, calling myself Mars Girl to constantly remind people that I feel I am different. I’m tired of hiding who I am so I’ve let myself out of my own closet to tell the world, “This is who I am; like it or leave it.”

It’s much harder to take on this sort of attitude as a homosexual because the backlash from the general public can be deadly. People have such a strong, irrational reaction to those whose sexual orientation or understanding of one’s gender is so radically different from their own. The religious conviction from fundamentalists that homosexuals and transgenders are damned does not make the situation any better. It’s a very sad situation and I completely empathize with anyone who has had to hide themselves in this manner. It’s a shame that people cannot accept people for who they are and show God’s love in a more positive manner. I believe that a person should have the right to walk down the street, arm in arm with the person they love, and not have to feel embarrassed, ashamed, or afraid of the public’s reaction to the sight. As a heterosexual person, I feel almost ashamed of my freedom to publicly show affection for a man I love without having to worry about reaction from those around me. I want to fight for the right for all people of any sexual orientation to have the same freedoms and lifestyle I’m automatically entitled to as a heterosexual.

Marilynne Robinson’s Writing Process, and Mine

Acclaimed novelist and social critic Marilynne Robinson, author of such books as Gilead and The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought, recently gave a fascinating interview to The Paris Review for their column “The Art of Fiction”. Topics covered include the importance of mystery to both religion and art, and how belief systems are often misused to draw lines between “good” and “bad” people rather than awakening our reverence for that mystery. An excerpt:

INTERVIEWER

Ames [a character in Gilead] believes that one of the benefits of religion is “it helps you concentrate. It gives you a good basic sense of what is being asked of you and also what you might as well ignore.” Is this something that your faith and religious practice has done for you?

ROBINSON

Religion is a framing mechanism. It is a language of orientation that presents itself as a series of questions. It talks about the arc of life and the quality of experience in ways that I’ve found fruitful to think about. Religion has been profoundly effective in enlarging human imagination and expression. It’s only very recently that you couldn’t see how the high arts are intimately connected to religion.

INTERVIEWER

Is this frame of religion something we’ve lost?

ROBINSON

There was a time when people felt as if structure in most forms were a constraint and they attacked it, which in a culture is like an autoimmune problem: the organism is not allowing itself the conditions of its own existence. We’re cultural creatures and meaning doesn’t simply generate itself out of thin air; it’s sustained by a cultural framework. It’s like deciding how much more interesting it would be if you had no skeleton: you could just slide under the door.

INTERVIEWER

How does science fit into this framework?

ROBINSON

I read as much as I can of contemporary cosmology because reality itself is profoundly mysterious. Quantum theory and classical physics, for instance, are both lovely within their own limits and yet at present they cannot be reconciled with each other. If different systems don’t merge in a comprehensible way, that’s a flaw in our comprehension and not a flaw in one system or the other.

INTERVIEWER

Are religion and science simply two systems that don’t merge?

ROBINSON

The debate seems to be between a naive understanding of religion and a naive understanding of science. When people try to debunk religion, it seems to me they are referring to an eighteenth-century notion of what science is. I’m talking about Richard Dawkins here, who has a status that I can’t quite understand. He acts as if the physical world that is manifest to us describes reality exhaustively. On the other side, many of the people who articulate and form religious expression have not acted in good faith. The us-versus-them mentality is a terrible corruption of the whole culture.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve written critically about Dawkins and the other New Atheists. Is it their disdain for religion and championing of pure science that troubles you?

ROBINSON

No, I read as much pure science as I can take in. It’s a fact that their thinking does not feel scientific. The whole excitement of science is that it’s always pushing toward the discovery of something that it cannot account for or did not anticipate. The New Atheist types, like Dawkins, act as if science had revealed the world as a closed system. That simply is not what contemporary science is about. A lot of scientists are atheists, but they don’t talk about reality in the same way that Dawkins does. And they would not assume that there is a simple-as-that kind of response to everything in question. Certainly not on the grounds of anything that science has discovered in the last hundred years.

The science that I prefer tends toward cosmology, theories of quantum reality, things that are finer-textured than classical physics in terms of their powers of description. Science is amazing. On a mote of celestial dust, we have figured out how to look to the edge of our universe. I feel instructed by everything I have read. Science has a lot of the satisfactions for me that good theology has.

INTERVIEWER

But doesn’t science address an objective notion of reality while religion addresses how we conceive of ourselves?

ROBINSON

As an achievement, science is itself a spectacular argument for the singularity of human beings among all things that exist. It has a prestige that comes with unambiguous changes in people’s experience—space travel, immunizations. It has an authority that’s based on its demonstrable power. But in discussions of human beings it tends to compare downwards: we’re intelligent because hyenas are intelligent and we just took a few more leaps. The first obligation of religion is to maintain the sense of the value of human beings. If you had to summarize the Old Testament, the summary would be: stop doing this to yourselves. But it is not in our nature to stop harming ourselves. We don’t behave consistently with our own dignity or with the dignity of other people. The Bible reiterates this endlessly.

The part of the interview that I found most reassuring, from a personal standpoint, was Robinson’s description of her intuitive, unstructured writing process. It has always been very hard for me to stop despising those aspects of my own temperament. In fact, I haven’t even tried until recently. For most of my writing life, I have been dogged by a sense of shame that my temperament was too flighty to be worthy of my gifts. What great things might I have already achieved if I wrote every day instead of whenever I felt like it–if I hammered down the plot of my novel and stuck to it–if I revised and workshopped my writing–if I didn’t become emotionally overwhelmed by my material and have to stop writing for months? Here’s what Robinson has to say about that:

INTERVIEWER

Do you plot your novels?

ROBINSON

I really don’t. There was a frame, of course, for Home, because it had to be symbiotic with Gilead. Aside from that, no. I feel strongly that action is generated out of character. And I don’t give anything a higher priority than character. The one consistent thing among my novels is that there’s a character who stays in my mind. It’s a character with complexity that I want to know better.

INTERVIEWER

The focus of the novel is Jack, but it’s told from Glory’s point of view. Did you ever consider putting it in his point of view?

ROBINSON

Jack is thinking all the time—thinking too much—but I would lose Jack if I tried to get too close to him as a narrator. He’s alienated in a complicated way. Other people don’t find him comprehensible and he doesn’t find them comprehensible.

INTERVIEWER

Is it hard to write a “bad” character?

ROBINSON

Calvin says that God takes an aesthetic pleasure in people. There’s no reason to imagine that God would choose to surround himself into infinite time with people whose only distinction is that they fail to transgress. King David, for example, was up to a lot of no good. To think that only faultless people are worthwhile seems like an incredible exclusion of almost everything of deep value in the human saga. Sometimes I can’t believe the narrowness that has been attributed to God in terms of what he would approve and disapprove….

INTERVIEWER

Does your faith ever conflict with your “regular life”?

ROBINSON

When I’m teaching, sometimes issues come up. I might read a scene in a student’s story that seems—by my standards—pornographic. I don’t believe in exploiting or treating with disrespect even an imagined person. But at the same time, I realize that I can’t universalize my standards. In instances like that, I feel I have to hold my religious reaction at bay. It is important to let people live out their experience of the world without censorious interference, except in very extreme cases.

INTERVIEWER

What is the most important thing you try to teach your students?

ROBINSON

I try to make writers actually see what they have written, where the strength is. Usually in fiction there’s something that leaps out—an image or a moment that is strong enough to center the story. If they can see it, they can exploit it, enhance it, and build a fiction that is subtle and new. I don’t try to teach technique, because frankly most technical problems go away when a writer realizes where the life of a story lies. I don’t see any reason in fine-tuning something that’s essentially not going anywhere anyway. What they have to do first is interact in a serious way with what they’re putting on a page. When people are fully engaged with what they’re writing, a striking change occurs, a discipline of language and imagination.

INTERVIEWER

Do you read contemporary fiction?

ROBINSON

I’m not indifferent to contemporary literature; I just don’t have any time for it. It’s much easier for my contemporaries to keep up with me than it is for me to keep up with them. They’ve all written fifteen books.

INTERVIEWER

What is your opinion of literary criticism?

ROBINSON

I know this is less true than it has been, but the main interest of criticism seems to be criticism. It has less to do with what people actually write. In journalistic criticism, the posture is too often that writers are making a consumer product they hope to be able to clean up on. I don’t think that living writers should be treated with the awe that is sometimes reserved for dead writers, but if a well-known writer whose work tends to garner respect takes ten years to write a novel and it’s not the greatest novel in the world, dismissiveness is not an appropriate response. An unsuccessful work might not seem unsuccessful in another generation. It may be part of the writer’s pilgrimage….

INTERVIEWER

Does writing come easily to you?

ROBINSON

The difficulty of it cannot be overstated. But at its best, it involves a state of concentration that is a satisfying experience, no matter how difficult or frustrating. The sense of being focused like that is a marvelous feeling. It’s one of the reasons I’m so willing to seclude myself and am a little bit grouchy when I have to deal with the reasonable expectations of the world.

INTERVIEWER

Do you keep to a schedule?

ROBINSON

I really am incapable of discipline. I write when something makes a strong claim on me. When I don’t feel like writing, I absolutely don’t feel like writing. I tried that work ethic thing a couple of times—I can’t say I exhausted its possibilities—but if there’s not something on my mind that I really want to write about, I tend to write something that I hate. And that depresses me. I don’t want to look at it. I don’t want to live through the time it takes for it to go up the chimney. Maybe it’s a question of discipline, maybe temperament, who knows? I wish I could have made myself do more. I wouldn’t mind having written fifteen books.

INTERVIEWER

Even if many of them were mediocre?

ROBINSON

Well, no.

Who Cares for the Reader’s Soul?

Among the many reasons I have found to avoid writing, or at least to avoid writing with any conviction, is the fear that my work would lead the reader astray. All truth comes from God, it is said, and therefore if I tell the truth as I see it, the end product will lead back to Him, without my needing to impose a Christian allegorical framework or engage my characters in theological conflicts.

The killer words there are as I see it. My vision is clouded by sin, so it is possible that if I write from the heart, what I’m really offering my readers is a glimpse into how far I am from God–or worse, persuading them to adopt my own faithless worldview.

It is no wonder that so much evangelical art is banal, since the stronger one’s belief in total depravity, the greater the resistance to departing from tried-and-true Biblical imagery. Of course, Catholics are no strangers to kitsch, but it’s always seemed to me that they had more of a campy sense of humor about it, connected to their refusal to let the sentimental entirely eclipse the grotesque.

Speaking of Catholics…I would like to believe what Flannery O’Connor says in this passage from “The Church and the Fiction Writer”, in Mystery and Manners, but I’m not sure if I should let myself off the hook that easily. On the other hand, what’s the alternative? I’m sure most people would rather read a good story than another hand-wringing post about why I don’t deserve to write one.

In this essay, O’Connor is disputing the conventional wisdom that religious truth and imaginative freedom are at odds. This view is shared by secular intellectuals and, ironically, by their Christian antagonists, who demand sanitized language and subject matter in their fiction. Both parties, she says, misunderstand the writer’s responsibility. Truth is embedded in the fallen reality of this world, not floating above it. The writer’s job is to describe this world, not to direct her readers’ spiritual lives.

Interestingly, O’Connor does not base this assurance on the “all truths lead to God” concept, which she might consider too akin to liberal optimism about personal authenticity and perspective-free knowledge. She would be more likely to cite St. Paul’s “many members, one body”: God wants us to know our role and develop the excellences appropriate to it, neither lording it over others nor taking on responsibilities outside our competence. O’Connor writes:

When fiction is made according to its nature, it should reinforce our sense of the supernatural by grounding it in concrete, observable reality. If the writer uses his eyes in the real security of his Faith, he will be obliged to use them honestly, and his sense of mystery, and acceptance of it, will be increased. To look at the worst will be for him no more than an act of trust in God; but what is one thing for the writer may be another for the reader. What leads the writer to his salvation may lead the reader into sin, and the Catholic writer who looks at this possibility directly looks the Medusa in the face and is turned to stone.

By now, anyone who has had the problem is equipped with Mauriac’s advice: “Purify the source.” And, along with it, he has become aware that while he is attempting to do that, he has to keep on writing. He becomes aware too of sources that, relatively speaking, seem amply pure, but from which come works that scandalize. He may feel that it is as sinful to scandalize the learned as the ignorant. In the end, he will either have to stop writing or limit himself to the concerns proper to what he is creating. It is the person who can follow neither of these courses who becomes the victim, not of the Church, but of a false conception of her demands.

The business of protecting souls from dangerous literature belongs properly to the Church. All fiction, even when it satisfies the requirements of art, will not turn out to be suitable for everyone’s consumption, and if in some instance the Church sees fit to forbid the faithful to read a work without permission, the author, if he is a Catholic, will be thankful that the Church is willing to perform this service for him. It means that he can limit himself to the demands of art.

The fact would seem to be that for many writers it is easier to assume a universal responsibility for souls than it is to produce a work of art…. (pp.148-49)

Ouch. That hits me right in my codependent little tush.

The fact is, dear readers, I don’t actually care about your souls as much as we all thought I did. What I really care about is not letting you see what a bad person I am, which might happen if I wrote honestly. Not even bad so much as foolish, self-indulgent, affected, unlikeable and gloomy. Honest badness has an artistic purity to it that is lacking in your garden-variety schmuck.

What O’Connor says about the reader’s soul is even more true about the writer’s. The battle is fought elsewhere. I have the authority to offer my personal vision of the world only because I personally am saved by grace–not because it’s necessarily accurate or because it will motivate you to get baptized. I can offer it but I can’t impose it. God has given me the right to show up. You, too.

Reginald Shepherd, 1963-2008

Reginald Shepherd, the acclaimed poet and essayist, died of cancer on Sept. 10. The Poetry Foundation has posted a moving tribute with comments from dozens of writers who were mentored or influenced by him.

I had fallen into a deep darkness this year due to a blurring of the boundaries between fiction, art, therapy, prayer, and real life. I was on a quest for that elusive thing called “reality”, which only God delivers, but I tried to conjure it on command between the pages of my notebook, only to find my characters wringing their hands about their own insubstantiality (a problem that was really mine, not theirs). Remembering the “high” of inspiration, when unprecedented closeness to God had coincided with a new gift for writing fiction, I thought writing was the cause rather than the effect of that vanished glory. I wanted justice to be done, but despaired that it was possible anywhere outside my imagination–then wept because my literary voodoo dolls didn’t cause real pain.

Shepherd’s last book of essays, Orpheus in the Bronx, shone a light that led me out of the tunnel. He championed the self-sufficiency of art against those who would make it the servant of a political agenda. If you want to change the world, go out and do something in the world, he said. Art is the place uncolonized by programs and definitions, where the ineffable intersects with the concrete, but is never wholly contained by it. Out of these imperfections of language comes a fruitful longing, a perpetual openness to new creation. As Shepherd wrote in his essay “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Coat: Nuances of a Theme by Stevens”:

The chasm between language and being, the inability of any naming to be the true name of the thing, is one that can be broached in many ways: at one extreme is scripture or dogma, which proclaims its names to be the literal equivalent of the thing; at the other is pure linguistic play (what Julia Kristeva calls unlimited semiosis), which neither claims nor seeks any such correspondence, for the rules of a game are unabashedly arbitrary. Between the two lies poetry, which combines the will to such an identity, the determination to speak the true names of things, with the awareness of the impossibility of such an endeavor, that the departure of the thing leaves us with only the name. That will is the guarantee of poetry’s seriousness; that awareness is the seal of its probity. (p.176)

I was in the same room as Reginald Shepherd at AWP this January and I was too self-conscious to say hello to him, and now he is dead. Folks, go out there and tell your favorite writers that they’ve made a difference in your life.

Stuart Kestenbaum: “Prayer for the Dead”

The column below is reprinted by permission from American Life in Poetry, a project of the Poetry Foundation.

American Life in Poetry: Column 181

BY TED KOOSER, U.S. POET LAUREATE, 2004-2006

Stuart Kestenbaum, the author of this week’s poem, lost his brother Howard in the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center. We thought it appropriate to commemorate the events of September 11, 2001, by sharing this poem. The poet is the director of the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts on Deer Isle, Maine.

Prayer for the Dead

The light snow started late last night and continued

all night long while I slept and could hear it occasionally

enter my sleep, where I dreamed my brother

was alive again and possessing the beauty of youth, aware

that he would be leaving again shortly and that is the lesson

of the snow falling and of the seeds of death that are in everything

that is born: we are here for a moment

of a story that is longer than all of us and few of us

remember, the wind is blowing out of someplace

we don’t know, and each moment contains rhythms

within rhythms, and if you discover some old piece

of your own writing, or an old photograph,

you may not remember that it was you and even if it was once you,

it’s not you now, not this moment that the synapses fire

and your hands move to cover your face in a gesture

of grief and remembrance.

American Life in Poetry is made possible by The Poetry Foundation (www.poetryfoundation.org), publisher of Poetry magazine. It is also supported by the Department of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Poem copyright (c) 2007 by Stuart Kestenbaum. Reprinted from “Prayers & Run-on Sentences,” Deerbook Editions, 2007, by permission of Stuart Kestenbaum. Introduction copyright (c) 2008 by The Poetry Foundation. The introduction’s author, Ted Kooser, served as United States Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 2004-2006. We do not accept unsolicited manuscripts.

Flannery O’Connor Appreciation Week (Part 3)

“Last spring I talked at [this school], and one of the girls asked me, ‘Miss O’Connor, why do you write?’ and I said, ‘Because I’m good at it,’ and at once I felt a considerable disapproval in the atmosphere. I felt that this was not thought by the majority to be a high-minded answer; but it was the only answer I could give. I had not been asked why I write the way I do, but why I write at all; and to that question there is only one legitimate answer.

“There is no excuse for anyone to write fiction for public consumption unless he has been called to do so by the presence of a gift. It is the nature of fiction not to be good for much unless it is good in itself.

“A gift of any kind is a considerable responsibility. It is a mystery in itself, something gratuitous and wholly undeserved, something whose real uses will probably always be hidden from us. Usually the artist has to suffer certain deprivations in order to use his gift with integrity. Art is a virtue of the practical intellect, and the practice of any virtue demands a certain asceticism and a very definite leaving-behind of the niggardly part of the ego. The writer has to judge himself with a stranger’s eye and a stranger’s severity. The prophet in him has to see the freak. No art is sunk in the self, but rather, in art the self becomes self-forgetful in order to meet the demands of the thing seen and the thing being made….

“St. Thomas [Aquinas] called art ‘reason in making.’ This is a very cold and very beautiful definition, and if it is unpopular today, it is because reason has lost ground among us. As grace and nature have been separated, so imagination and reason have been separated, and this always means an end to art. The artist uses his reason to discover an answering reason in everything he sees. For him, to be reasonable is to find, in the object, in the situation, in the sequence, the spirit which makes it itself. This is not an easy or simple thing to do. It is to intrude upon the timeless, and that is only done by the violence of a single-minded respect for the truth….

“One thing that is always with the writer–no matter how long he has written or how good he is–is the continuing process of learning to write. As soon as the writer ‘learns to write,’ as soon as he knows what he is going to find, and discovers a way to say what he knew all along, or worse still, a way to say nothing, he is finished. If a writer is any good, what he makes will have its source in a realm much larger than that which his conscious mind can encompass and will always be a greater surprise to him than it can ever be to his reader.”

–“The Nature and Aim of Fiction,” in Mystery and Manners (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969), pp. 81-83.