Hundreds of people braved the freezing winds and icy steps of Boston City Hall to rally for GLBT rights this past Saturday. In addition to pushing for the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, speakers advocated for passage of a federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act and urged Massachusetts to add gender identity and expression to its existing anti-discrimination law. (The latter bill will be filed in the Mass. legislature on Jan. 14; contact your legislators here.)

Among the speakers were Cambridge Mayor E. Denise Simmons, Rep. Barney Frank, Boston Mayor Thomas M. Menino, and the Rev. Jeffrey Mello from Christ Church Cambridge, the Episcopal Church in Harvard Square. After the rally, we marched through downtown Boston, ending up in a Methodist church where we were treated to passionate slam poetry by award-winning performer James Caroline.

Below is a video (52 minutes) of the rally, recorded by my husband Adam Cohen with his ever-present Flip camera.

Category Archives: GLBT

Nationwide Protest Against the “Defense of Marriage Act” on Jan. 10

Activists nationwide will be gathering on Jan. 10 to protest the federal Defense of Marriage Act and gather petition signatures asking President-elect Obama to support its repeal. My husband and I will be at the Boston event, 1:30-4:30 PM in front of City Hall. To find the event in your city and print out the official petition form, visit Join the Impact.

DOMA, passed in 1996, defined marriage as between a man and a woman for purposes of all federal laws, and decreed that states did not have to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states. Normally, the Constitution requires states to give “full faith and credit” to the laws of other states.

This means, for instance, that a woman covered by her domestic partner’s insurance must pay federal income tax on those benefits, where a heterosexual married couple would not. Same-sex couples can’t file joint tax returns or inherit as surviving spouses. A man might not be allowed to visit his partner in the hospital because the state where he fell sick treats them as legal strangers, even if they’re married in their home state. A straight person can get a green card for his or her immigrant spouse, but there’s no such mechanism for same-sex couples. These are just a few examples of the 1,100 rights and privileges that we heterosexual couples take for granted.

DOMA’s title is a misnomer because it confers no new protections on straight married couples, nor removes any threat to the legal privileges we already enjoy. It should have been called the “Deprivation of Marriage Act”.

Even Christians who oppose gay marriage should rethink whether this is a proper use of state power. Disadvantaging same-sex couples has no effect on how we live our lives. It only “defends” our specialness at the expense of a minority group. Isn’t marriage worthwhile in itself? Do we really need the incentive of feeling superior to others?

Jesus didn’t say anything about homosexuality, but he sure had a lot to say against people whose righteousness depended on invidious comparisons. I’m thinking especially of the parable of the laborers in the vineyard (Matt. 20:1-16), as well as the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9-14).

So, DOMA defenders, what’s it really about? Are you hoping that if you make gay marriage difficult enough, they’ll give up and become straight?

I’ll let Jon Stewart have the last word on this one, in this Daily Show interview from December 2008 with former Arkansas governor and GOP presidential candidate Mike Huckabee. “Religion is far more of a choice than homosexuality…and the protections that we have for religion…talk about a lifestyle choice!” Stewart observes, adding, “It would be redefining a word, and it feels like semantics is cold comfort when it comes to humanity.”

Amen.

I Came Here for an Argument

This video will explain why I turned off the comments mechanism on this blog:

Great humor often contains insights into serious issues. What is the difference between an argument and mere contradiction or abuse? And what motivates us to respect some arguments, while blocking out the possibility that others might be legitimate?

We may resort to bare contradiction when it’s too frightening to face new interpretations of a text that once seemed clear to us. Refusal to engage with the argument can be a way of denying that there could be other possibilities. Sadly, it also bypasses an opportunity for self-knowledge.

As long as we pretend that there is only one possible viewpoint, we don’t have to examine the desires, fears, vanities, or misunderstandings that spur us to cling to that viewpoint. Nor do we confront the power imbalance between us and the questioners–the privilege that puts us in a position to interpret their lives in the first place, rather than the other way around.

Abuse takes this strategy a step farther. Because ours is the only possible interpretation, anyone who disagrees must be disobedient or perverted. Our own anger (or revulsion, or fear of losing something special to us) becomes objectified, masked by the authority of the text. It is not a personal feeling for which we must take responsibility, whereas the other side has only selfish personal feelings.

Before we as Christians can conduct a fruitful and faithful discussion about issues on which we disagree, we must be honest with ourselves and one another about the passions behind those issues, and consider which emotions are the most appropriate guides to choosing between one interpretation and another. Perfect love casts out fear.

“Nature” a Moving Target for Theologians

Austen Ivereigh, a columnist on the website of America: The National Catholic Weekly, made some insightful comments on the Church’s changing understanding of what is “natural” in his Christmas Eve column, “Gays, Galileo, and the Message of the Manger”. Excerpts:

The BBC has the correct headline on Pope Benedict’s curial speech story. “Pope attacks blurring of gender” is far more accurate than all those headlines claiming that “saving gay people is as important as saving the rainforests”…

The essential theological point in the Pope’s intriguing address is that going green while erasing God from Creation is a contradiction. Nature, he says is “the gift of the Creator, with certain intrinsic rules that offer us an orientation we must respect as administrators of creation.”

And he goes on: “That which is often expressed and understood by the term ‘gender’ in the end amounts to the self-emancipation of the human person from creation and from the Creator. Human beings want to do everything by themselves, and to control exclusively everything that regards them. But in this way, the human person lives against the truth, against the Creator Spirit.”

It’s worth placing this papal observation alongside the tribute Benedict XVI paid last Sunday to Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) on the 400th anniversary of the condemned astronomer’s telescope.

Galileo, you will recall, was declared a heretic by the seventeenth-century Church for supporting Nicholas Copernicus’ discovery that the Earth revolved around the sun (church teaching at the time placed the Earth at the centre of the universe). For centuries the Galileo condemnation has been used by secularists as a symbol of all that is incompatible between faith and science.

Last weekend, the Vatican sought to reverse that symbolism, building on Pope John Paul II’s 1992 apology and dusting off Galileo as a shining representative of faith and reason working together….

…I can’t help but spot an irony.

Galileo was condemned, at the time, because he was held to subvert the God-ordained nature of things. One can imagine Pope Urban VIII in 1633 using words similar to Pope Benedict’s to the Curia: that nature has “certain intrinsic rules that offer us an orientation we must respect as administrators of creation.”

But it wasn’t long before the “intrinsic rules” were overturned by the evidence. It turned out that putting the Earth at the centre of the universe was not God’s plan at all.

Mark Dowd, gay ex-Dominican and strategist for the Christian environmental group Operation Noah, is widely quoted in UK press reports as saying that in his curial speech Benedict XVI betrayed “a lack of openness to the complexity of creation” — in other words, that papal faith in the fixity of male-female gender roles may be misplaced.

At the moment, there seems little room in the Catholic Church’s “human ecology” for a possible divine purpose for homosexuality — just as in the seventeenth century there wasn’t much space for the idea that God has arranged the universe with the sun at its centre. It would be syllogistic to suggest that because the Church was wrong on the second it will turn out to be wrong on the first.

But it’s striking how the homosexual orientation appears in church teaching as “intrinsically disordered” — in other words, as contrary to the way God arranged the universe — in the same way as the Copernican view appeared in the seventeenth century.

And it isn’t a bad thought, at Christmas, to remember that the Creator of the Universe is capable of subverting its laws for the sake of His creatures.

Things are never so finally fixed that God can’t rearrange it all. The arrogance of scientists, of clergy, of the wise, our own arrogance — all get dethroned tonight by the Great Event: the manger-child, born of a refugee couple and the Holy Spirit, in a cave, in a place somewhere off the map, to where the centre of the Universe quietly relocates. Happy Christmas.

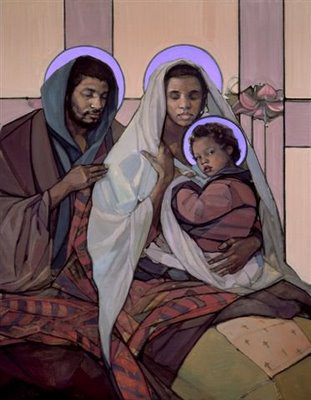

AltXmas Art Envisions Holy Family of Color

Kittredge Cherry’s Jesus in Love blog is running a series of artworks that look at the imagery of the Christmas season through the lens of poverty, racial and gender justice. The beautiful and thought-provoking images are accompanied by Kitt’s daily Advent meditations. She’s kindly given me permission to reproduce today’s painting, “The Holy Family” by Janet McKenzie.

Copyright 2007 Janet McKenzie

Collection of Loyola School, New York, NY

About this painting, Kitt writes:

…Sometimes McKenzie’s art sparks controversy. Her androgynous African American “Jesus of the People” painting caused an international uproar after Sister Wendy of PBS chose it to represent Christ in the new millennium in 2000. However, McKenzie says that the responses to “The Holy Family” have been accepting and positive, perhaps because it was commissioned and wholeheartedly supported by the Loyola School in New York.

“As a school run by the Jesuits, it was important to them to have such an image, one that reflects their ethical and inclusive beliefs,” McKenzie explains. “ ‘The Holy Family’ celebrates Mary, Joseph and Jesus as a family of color. I feel as an artist that it is vital to put loving sacred art — art that includes rather than excludes — into the world, in order to remind that we are all created equally and beautifully in God’s likeness. Everyone, especially those traditionally marginalized, needs the comfort derived by finding one’s own image positively reflected back in iconic art. By honoring difference we are ultimately reminded of our inherent similarities.”

The Vermont-based artist had built a successful career painting women who looked like herself, fair and blonde, before her breakthrough with “Jesus of the People.” At that time she wanted to create a truly inclusive image that would touch her nephew, an African American teenager. “The Holy Family” continues the process of embracing everybody in one human family created in God’s image.

Read the full post here.

Newsweek Makes Christian Case for Marriage Equality

Newsweek has been bombarded with mass emails from conservative churches who were outraged by this article. To send your message of support, see this page on the Human Rights Campaign website.

The debate over scriptural views of homosexuality makes many people afraid that they will have to choose between their faith and their relationships. Conservative friends have told me that I am cutting myself off from the orthodox Christian community by attending an inclusive church. Meanwhile, some in that church are skittish about its historic doctrines, afraid that tradition cannot be disentangled from a legacy of institutional oppression.

Fortunately, I’m not the only one who hasn’t given up hopes of an inclusive orthodoxy. Newsweek ran a brave and controversial cover story last week: Our Mutual Joy: The Religious Case for Gay Marriage, by Lisa Miller. Highlights:

In the Old Testament, the concept of family is fundamental, but examples of what social conservatives would call “the traditional family” are scarcely to be found. Marriage was critical to the passing along of tradition and history, as well as to maintaining the Jews’ precious and fragile monotheism. But as the Barnard University Bible scholar Alan Segal puts it, the arrangement was between “one man and as many women as he could pay for.” Social conservatives point to Adam and Eve as evidence for their one man, one woman argument—in particular, this verse from Genesis: “Therefore shall a man leave his mother and father, and shall cleave unto his wife, and they shall be one flesh.” But as Segal says, if you believe that the Bible was written by men and not handed down in its leather bindings by God, then that verse was written by people for whom polygamy was the way of the world. (The fact that homosexual couples cannot procreate has also been raised as a biblical objection, for didn’t God say, “Be fruitful and multiply”? But the Bible authors could never have imagined the brave new world of international adoption and assisted reproductive technology—and besides, heterosexuals who are infertile or past the age of reproducing get married all the time.)

Ozzie and Harriet are nowhere in the New Testament either. The biblical Jesus was—in spite of recent efforts of novelists to paint him otherwise—emphatically unmarried. He preached a radical kind of family, a caring community of believers, whose bond in God superseded all blood ties. Leave your families and follow me, Jesus says in the gospels. There will be no marriage in heaven, he says in Matthew. Jesus never mentions homosexuality, but he roundly condemns divorce (leaving a loophole in some cases for the husbands of unfaithful women).

The apostle Paul echoed the Christian Lord’s lack of interest in matters of the flesh. For him, celibacy was the Christian ideal, but family stability was the best alternative. Marry if you must, he told his audiences, but do not get divorced. “To the married I give this command (not I, but the Lord): a wife must not separate from her husband.” It probably goes without saying that the phrase “gay marriage” does not appear in the Bible at all.

If the bible doesn’t give abundant examples of traditional marriage, then what are the gay-marriage opponents really exercised about? Well, homosexuality, of course—specifically sex between men. Sex between women has never, even in biblical times, raised as much ire. In its entry on “Homosexual Practices,” the Anchor Bible Dictionary notes that nowhere in the Bible do its authors refer to sex between women, “possibly because it did not result in true physical ‘union’ (by male entry).” The Bible does condemn gay male sex in a handful of passages. Twice Leviticus refers to sex between men as “an abomination” (King James version), but these are throwaway lines in a peculiar text given over to codes for living in the ancient Jewish world, a text that devotes verse after verse to treatments for leprosy, cleanliness rituals for menstruating women and the correct way to sacrifice a goat—or a lamb or a turtle dove. Most of us no longer heed Leviticus on haircuts or blood sacrifices; our modern understanding of the world has surpassed its prescriptions. Why would we regard its condemnation of homosexuality with more seriousness than we regard its advice, which is far lengthier, on the best price to pay for a slave?

Paul was tough on homosexuality, though recently progressive scholars have argued that his condemnation of men who “were inflamed with lust for one another” (which he calls “a perversion”) is really a critique of the worst kind of wickedness: self-delusion, violence, promiscuity and debauchery. In his book “The Arrogance of Nations,” the scholar Neil Elliott argues that Paul is referring in this famous passage to the depravity of the Roman emperors, the craven habits of Nero and Caligula, a reference his audience would have grasped instantly. “Paul is not talking about what we call homosexuality at all,” Elliott says. “He’s talking about a certain group of people who have done everything in this list. We’re not dealing with anything like gay love or gay marriage. We’re talking about really, really violent people who meet their end and are judged by God.” In any case, one might add, Paul argued more strenuously against divorce—and at least half of the Christians in America disregard that teaching.

Religious objections to gay marriage are rooted not in the Bible at all, then, but in custom and tradition (and, to talk turkey for a minute, a personal discomfort with gay sex that transcends theological argument). Common prayers and rituals reflect our common practice: the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer describes the participants in a marriage as “the man and the woman.” But common practice changes—and for the better, as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “The arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.” The Bible endorses slavery, a practice that Americans now universally consider shameful and barbaric. It recommends the death penalty for adulterers (and in Leviticus, for men who have sex with men, for that matter). It provides conceptual shelter for anti-Semites. A mature view of scriptural authority requires us, as we have in the past, to move beyond literalism. The Bible was written for a world so unlike our own, it’s impossible to apply its rules, at face value, to ours.

Marriage, specifically, has evolved so as to be unrecognizable to the wives of Abraham and Jacob. Monogamy became the norm in the Christian world in the sixth century; husbands’ frequent enjoyment of mistresses and prostitutes became taboo by the beginning of the 20th. (In the NEWSWEEK POLL, 55 percent of respondents said that married heterosexuals who have sex with someone other than their spouses are more morally objectionable than a gay couple in a committed sexual relationship.) By the mid-19th century, U.S. courts were siding with wives who were the victims of domestic violence, and by the 1970s most states had gotten rid of their “head and master” laws, which gave husbands the right to decide where a family would live and whether a wife would be able to take a job. Today’s vision of marriage as a union of equal partners, joined in a relationship both romantic and pragmatic, is, by very recent standards, radical, says Stephanie Coontz, author of “Marriage, a History.”…

…We cannot look to the Bible as a marriage manual, but we can read it for universal truths as we struggle toward a more just future. The Bible offers inspiration and warning on the subjects of love, marriage, family and community. It speaks eloquently of the crucial role of families in a fair society and the risks we incur to ourselves and our children should we cease trying to bind ourselves together in loving pairs. Gay men like to point to the story of passionate King David and his friend Jonathan, with whom he was “one spirit” and whom he “loved as he loved himself.” Conservatives say this is a story about a platonic friendship, but it is also a story about two men who stand up for each other in turbulent times, through violent war and the disapproval of a powerful parent…

…In addition to its praise of friendship and its condemnation of divorce, the Bible gives many examples of marriages that defy convention yet benefit the greater community. The Torah discouraged the ancient Hebrews from marrying outside the tribe, yet Moses himself is married to a foreigner, Zipporah. Queen Esther is married to a non-Jew and, according to legend, saves the Jewish people. Rabbi Arthur Waskow, of the Shalom Center in Philadelphia, believes that Judaism thrives through diversity and inclusion. “I don’t think Judaism should or ought to want to leave any portion of the human population outside the religious process,” he says. “We should not want to leave [homosexuals] outside the sacred tent.” The marriage of Joseph and Mary is also unorthodox (to say the least), a case of an unconventional a

rrangement accepted by society for the common good. The boy needed two human parents, after all.

In the Christian story, the message of acceptance for all is codified. Jesus reaches out to everyone, especially those on the margins, and brings the whole Christian community into his embrace. The Rev. James Martin, a Jesuit priest and author, cites the story of Jesus revealing himself to the woman at the well— no matter that she had five former husbands and a current boyfriend—as evidence of Christ’s all-encompassing love. The great Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann, emeritus professor at Columbia Theological Seminary, quotes the apostle Paul when he looks for biblical support of gay marriage: “There is neither Greek nor Jew, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Jesus Christ.” The religious argument for gay marriage, he adds, “is not generally made with reference to particular texts, but with the general conviction that the Bible is bent toward inclusiveness.”

The practice of inclusion, even in defiance of social convention, the reaching out to outcasts, the emphasis on togetherness and community over and against chaos, depravity, indifference—all these biblical values argue for gay marriage. If one is for racial equality and the common nature of humanity, then the values of stability, monogamy and family necessarily follow. Terry Davis is the pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Hartford, Conn., and has been presiding over “holy unions” since 1992. “I’m against promiscuity—love ought to be expressed in committed relationships, not through casual sex, and I think the church should recognize the validity of committed same-sex relationships,” he says.

Still, very few Jewish or Christian denominations do officially endorse gay marriage, even in the states where it is legal. The practice varies by region, by church or synagogue, even by cleric. More progressive denominations—the United Church of Christ, for example—have agreed to support gay marriage. Other denominations and dioceses will do “holy union” or “blessing” ceremonies, but shy away from the word “marriage” because it is politically explosive. So the frustrating, semantic question remains: should gay people be married in the same, sacramental sense that straight people are? I would argue that they should. If we are all God’s children, made in his likeness and image, then to deny access to any sacrament based on sexuality is exactly the same thing as denying it based on skin color—and no serious (or even semiserious) person would argue that. People get married “for their mutual joy,” explains the Rev. Chloe Breyer, executive director of the Interfaith Center in New York, quoting the Episcopal marriage ceremony. That’s what religious people do: care for each other in spite of difficulty, she adds. In marriage, couples grow closer to God: “Being with one another in community is how you love God. That’s what marriage is about.”

I commend Newsweek for their courage and thoroughness in giving a voice to inclusive interpretations of scripture. But frankly, I’m getting fed up with trying to prove that “hey, we’re Christians too!” The Biblical analysis above won’t convince everyone that this is the only legitimate way to read the verses referring to same-sex intercourse–because it isn’t. It is, however, a legitimate reading. Can we all just move on now?

Most Bible passages admit of several interpretations if they are talking about anything remotely interesting. Christians can spin out book-length arguments for and against infant baptism; the Eucharist as Real Presence or symbol; six-day Creation; the timing of the apocalypse; free will versus predestination; pacifism versus just-war theory; whether Jesus was a communist; and on and on.

These are important issues, affecting many more people than the 10% of the population who are homosexual. We may not be able to gather all views under a single denominational umbrella. Yet somehow Arminians manage to recognize that Calvinists are still Christians. Baptists acknowledge Catholics’ sincere discipleship, even if they don’t take communion together.

But dare to suggest that there’s more than one way to read a half-dozen little verses about same-sex intimacy, and your obedience to God and Scripture is immediately called into question. You’re not just wrong, you’re disobedient. You don’t belong to the body of Christ. There can’t be any evidence of the Holy Spirit in your life.

I’d like to know why the burden of proof is on us to show that these verses should be narrowly construed, rather than on anti-gay Christians to justify their preference for laying the heaviest possible burden on an outcast minority. Why does it seem like they’re actively looking for arguments to maintain the status quo? Shouldn’t our choice of hermeneutic be driven by love and charity?

For all my fellow queer families out there: We can’t wait around for permission to believe that God’s grace belongs to us equally. We have to claim it for ourselves, within ourselves. Yes, “be prepared to give a reason for the hope that is in you.” But remember that we’re the body of Christ now, and no one can take that away from us.

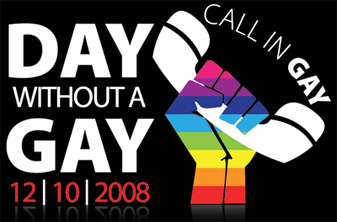

Call In Gay to Work on Dec. 10

Day Without a Gay is a nationwide strike and economic boycott by the LGBT community and their straight allies, in support of equal marriage rights for all Americans. The strike will take place on Dec. 10, International Human Rights Day. Instead of going to work or shopping on that day, participants are encouraged to volunteer for their local LGBT or human rights organizations. Here’s the information from the email announcement:

WHY? To raise awareness that LGBT workers, business owners, consumers and taxpayers contribute over $700 billion to the American economy. We are lesbian and gay Americans and we deserve the same rights as all other Americans, including the right to get married.

WHERE? All across the United States.

HOW?

Strike! Call in gay. That means shut down your business, call in sick, take the day off.

Boycott! Don’t buy anything, spend money or support the economy.

Participate! Give back, fight back or help roll back marriage discrimination. Go to www.daywithoutagay.org to volunteer, petition or protest.

WHY THE NAME “A DAY WITHOUT GAYS”? The name was inspired by the film A DAY WITHOUT A MEXICAN and the nationwide strike in 2006 called A DAY WITHOUT IMMIGRANTS that protested against proposed immigration laws.

WHY STRIKE NOW? One day won’t destroy the economy, but it will raise awareness that we are serious about getting our rights. Also, strikes and boycotts are more effective in an economic downturn because business owners have more to lose.

WHY A STRIKE AND A BOYCOTT? These tactics have been successful in the past, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the anti-apartheid boycotts. Their actions often came at a great sacrifice but they were willing to risk everything for their rights.

WHAT IF I WILL GET FIRED? In fact, many states still do not have employment non-discrimination laws for gays and lesbians. If you are in fear of getting fired, go to work, but you can participate in the boycott by not consuming. Pack a lunch!

Visit the Day Without a Gay organizing page on the social networking site WetPaint to find volunteering and activism opportunities in your area.

Resources for World AIDS Day

Today, Dec. 1, is the 20th anniversary of World AIDS Day, an international day of awareness about AIDS prevention and treatment. Here’s a small sampling of resources I’ve found worthy of attention:

Mthatha Mission

Jesse Zink, a graduate of our church’s youth program, is serving as a missionary with the Episcopal Church’s Young Adult Service Corps. He’s currently stationed at the Itipini Clinic in Mthatha, one of the poorest villages in South Africa, where he cares for HIV patients and their families. His stories from the front lines are filled with warmth, humor, sadness, and awareness of global inequalities.

Partners In Health

Before Paul Farmer started his free clinic for HIV and tuberculosis patients in Haiti, world health organizations wrote off these desperately poor areas as presenting problems too intractable for aid workers to solve. Farmer’s revolutionary model is based on hands-on involvement in patients’ lives, addressing not only their medical needs but the economic and social injustices that are the underlying cause of their plight. Their website says, “Our mission is to provide a preferential option for the poor in health care.” Tracy Kidder’s book Mountains Beyond Mountains is an excellent introduction to PIH’s history and worldwide achievements.

Jesus in Love

Armando Lopez’ painting “El Martir”, a reinterpretation of St. Sebastian, is posted at Jesus in Love, Kittredge Cherry’s always-provocative website exploring queer spirituality and the arts.

MSNBC’s Keith Olbermann Speaks Out Against Prop 8

This may be the most moving speech for equal marriage rights I’ve ever heard. Olbermann, a straight ally, sounded like he was on the verge of tears several times.

An excerpt from the transcript:

I keep hearing this term “re-defining” marriage. If this country hadn’t re-defined marriage, black people still couldn’t marry white people. Sixteen states had laws on the books which made that illegal in 1967. 1967.

The parents of the President-Elect of the United States couldn’t have married in nearly one third of the states of the country their son grew up to lead. But it’s worse than that. If this country had not “re-defined” marriage, some black people still couldn’t marry black people. It is one of the most overlooked and cruelest parts of our sad story of slavery. Marriages were not legally recognized, if the people were slaves. Since slaves were property, they could not legally be husband and wife, or mother and child. Their marriage vows were different: not “Until Death, Do You Part,” but “Until Death or Distance, Do You Part.” Marriages among slaves were not legally recognized.

You know, just like marriages today in California are not legally recognized, if the people are gay.

And uncountable in our history are the number of men and women, forced by society into marrying the opposite sex, in sham marriages, or marriages of convenience, or just marriages of not knowing, centuries of men and women who have lived their lives in shame and unhappiness, and who have, through a lie to themselves or others, broken countless other lives, of spouses and children, all because we said a man couldn’t marry another man, or a woman couldn’t marry another woman. The sanctity of marriage.

How many marriages like that have there been and how on earth do they increase the “sanctity” of marriage rather than render the term, meaningless?

What is this, to you? Nobody is asking you to embrace their expression of love. But don’t you, as human beings, have to embrace… that love? The world is barren enough.

It is stacked against love, and against hope, and against those very few and precious emotions that enable us to go forward. Your marriage only stands a 50-50 chance of lasting, no matter how much you feel and how hard you work.

And here are people overjoyed at the prospect of just that chance, and that work, just for the hope of having that feeling. With so much hate in the world, with so much meaningless division, and people pitted against people for no good reason, this is what your religion tells you to do? With your experience of life and this world and all its sadnesses, this is what your conscience tells you to do?

With your knowledge that life, with endless vigor, seems to tilt the playing field on which we all live, in favor of unhappiness and hate… this is what your heart tells you to do? You want to sanctify marriage? You want to honor your God and the universal love you believe he represents? Then Spread happiness—this tiny, symbolic, semantical grain of happiness—share it with all those who seek it. Quote me anything from your religious leader or book of choice telling you to stand against this. And then tell me how you can believe both that statement and another statement, another one which reads only “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Read the entire transcript here.

Hundreds Attend “Join the Impact” Gay Marriage Rally in Northampton

Supporters of equal marriage rights held nationwide rallies yesterday, a grass-roots effort organized by the social networking group Join the Impact. Northampton’s event was coordinated by Kate Martini, whom you can see below in the video (blonde hair, red sweater). She did a wonderful job selecting a diverse group of speakers, gay and straight, who spoke from the heart about how the denial of anyone’s civil rights affects us all. It was my privilege to be one of them.

Upbeat, empowering entertainment was provided by the rainbow-clad Raging Grannies, the OffBeat women’s drumming circle, and the Amherst Unitarian Universalist choir. The Daily Hampshire Gazette newspaper estimated that 500 people attended.

Below are some photos from yesterday’s event. If you attended this rally, or a Join the Impact rally in another city, you’re encouraged to upload your pictures and videos to the Join the Impact website.

Signs of the times:

This is the Justice of the Peace who performed the first same-sex weddings in Northampton after gay marriage was legalized in 2004:

Our first speaker, Lorelei Erisis:

Shannon Weber (in the middle) is a Mt. Holyoke student who married her wife (on the right) in California earlier this year:

Rev. Heath, a hospice chaplain, speaks about how her faith in a loving God inspires her support for equal rights:

Telling the story of my queer family:

Our local activist choir:

The OffBeat drummers start a rousing chant for justice (that’s me waving the pride flag in the background):

The Amherst UU’s lead us in the Holly Near song, “We Are a Gentle, Angry People”:

The Rev. Tinker Donnelly from the Unity Church in Greenfield:

Our local MassEquality organizer, Jack Hornor:

Kate closes the rally with a joyful chorus of “Yes We Can!”